Charlie Kaufman’s Trans Trilogy: Being John Malkovich (1999); Synecdoche NY (2009); Antkind (2020)

This week: an examination of Being John Malkovich at 25, by a trans woman for whom it provoked a lot of Gender Dysphoria, aged 20, but also helped (a little) to think it through

Here in the woke 2020s, where gender ideology is rammed down our throats by leftie liberals determined to transify everyone, there can’t be a man, woman, or child who isn’t aware that The Matrix (1999) is a trans allegory because Lana & Lilly Wachowski said so. For those of us, though, who had a lot of time at the end of the last millennium for avant-garde cinema between lectures in our Humanities degrees (when we should have been studying STEM to become “wealth-creators”), Kaufman’s Malkovich was the first real sighting of genuinely sophisticated trans representation that didn’t entail someone being abducted and skinned.

(Obviously, I jest but I re-watched The Matrix this January, the same month I “went full-time” as a trans woman, after 18 months of Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy, and I still think it works better as an allegory of overcoming capitalist false-consciousness in which gender is curiously flattened rather than being explored in any depth; at the time, critics claimed you needed to read Baudrillard to fully understand it but I already had, didn’t see anything especially clever about what the Sisters-W were doing, and just came out of the cinema wanting to start a fight. In a good way. But we’ll talk about my Fight Club phase of running from Gender Dysphoria another time…)

PART ONE: BEING JOHN MALKOVICH

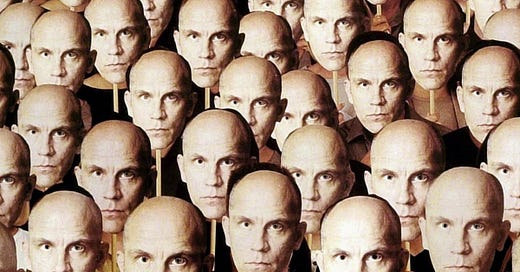

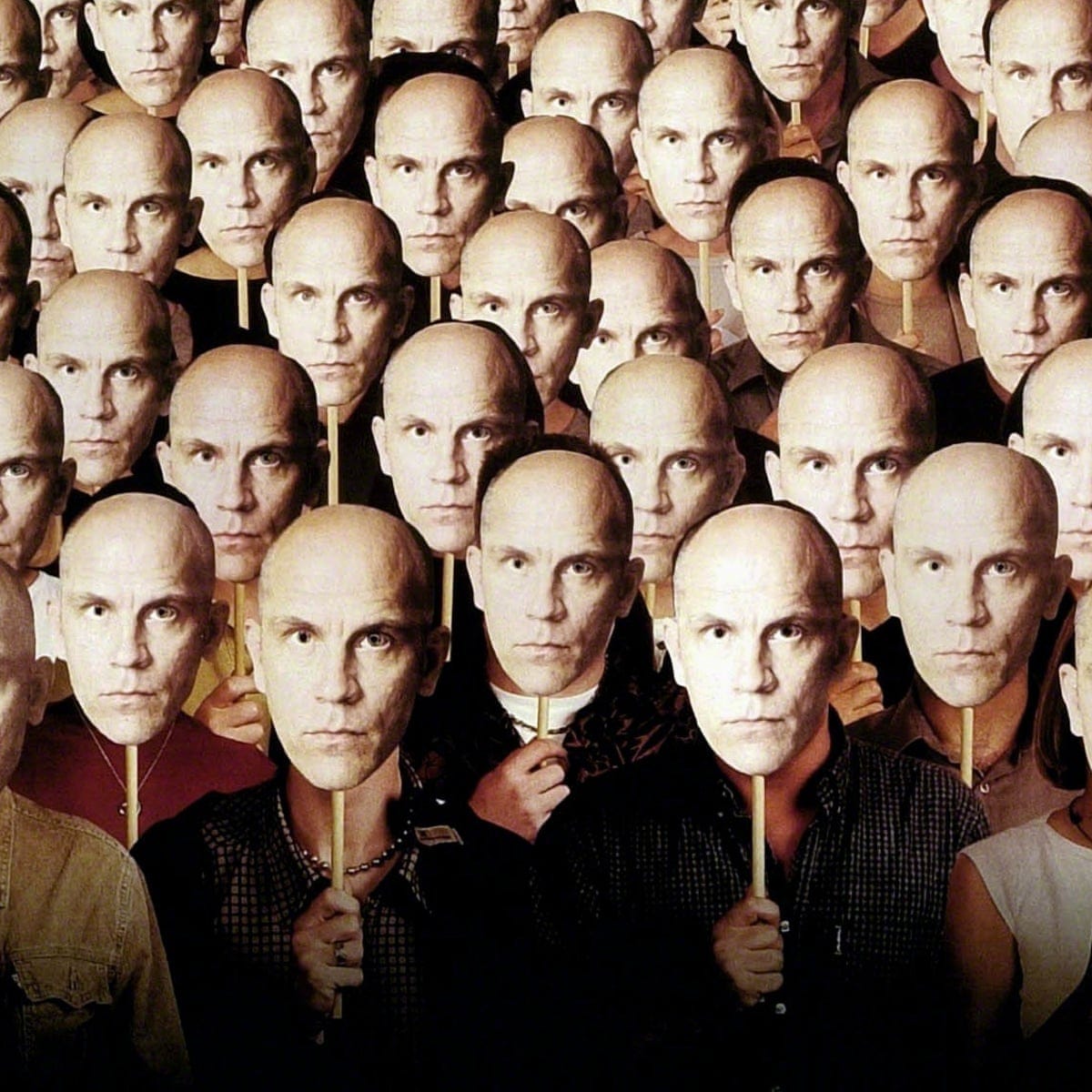

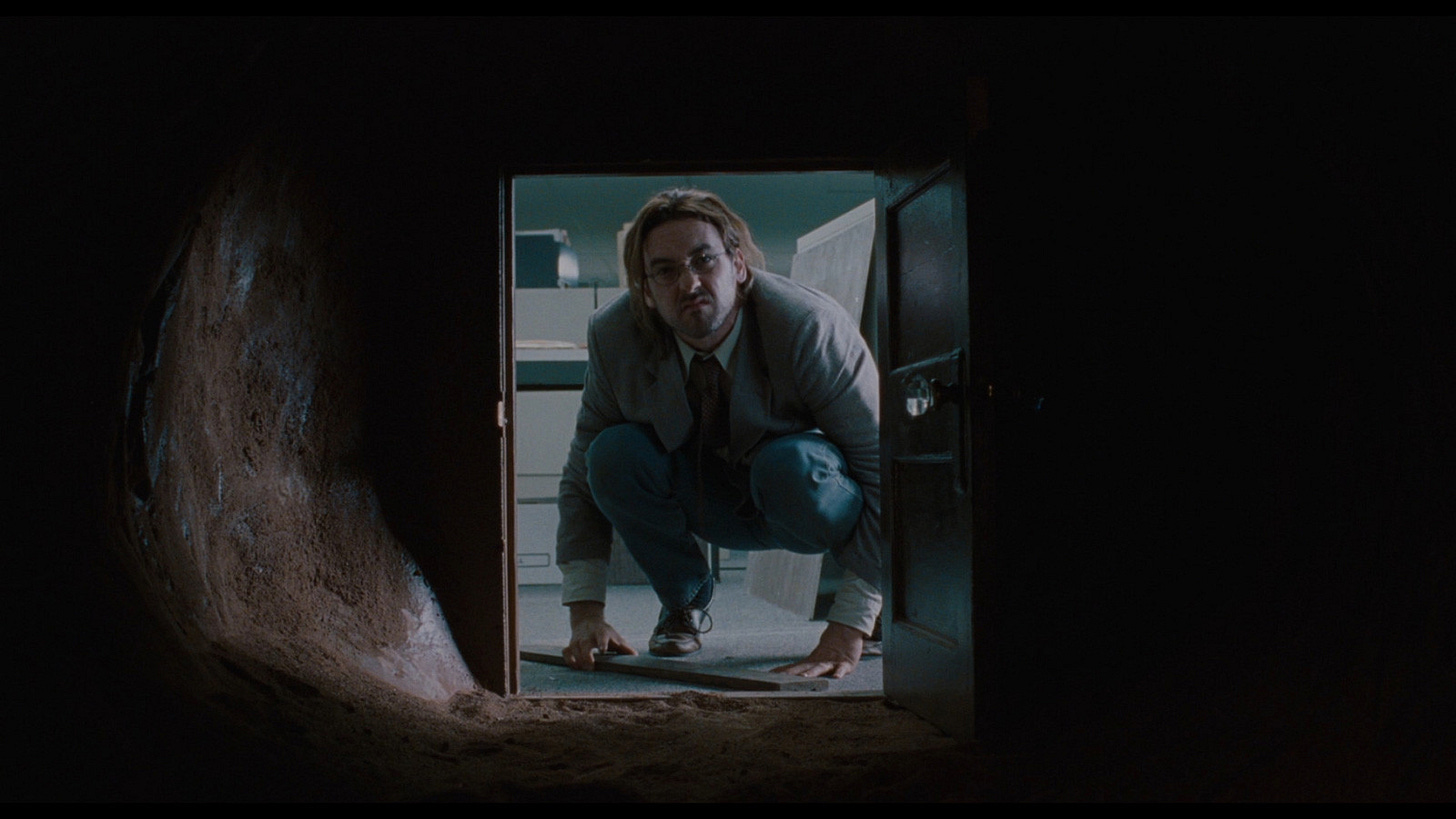

For those of you who don’t know, Malkovich is the story of a struggling puppeteer, Craig Schwartz, who takes a job as a filing clerk in an office on the 7½th floor (that’s right: the Seven-and-a-Half-th; the floor between floors, the liminal zone between categories, you get the drill) where he discovers a portal into John Malkovich’s subconscious, allowing him to experience the life of a critically acclaimed actor, albeit the kinda-funny-looking Malkovich. Having fallen for the enthralling femme fatale Maxine (played by Catherine Keener), Craig (played by John Cusack) goes into business exploiting the desire of lonely, mediocre people to be someone else. Schwartz only wants to sleep with Maxine, who only tolerates him for the sake of a commercial opportunity, but a further complication comes in the form of his wife Lotte (played by Cameron Diaz) whose own trip through Malkovich’s portal intrigues Maxine: inviting Malkovich on a date while Lotte is inside him, she discovers a kink for Lotte’s “feminine longing” (51:00) when she senses it behind the eyes of a male body.

Now, those who know the film may quibble where the allegory is situated in the plot. Lotte explicitly speculates that she might be a transsexual after her first trip through the portal in which she enjoys the feeling of hairy legs and (implicitly) a penis while Malkovich takes a shower, and then the sight of a “powerful…masculine” body in the mirror, saying she wants to speak to her doctor about Sex Reassignment Surgery (41:00). The scene is played for laughs with Craig protesting that Dr Feldman is her allergist, as if this is another in a long list of neurotic behaviours (like adopting animals with psychiatric problems in lieu of children) that he has to endure, having burdened himself with a wife who looks like she’s been dragged through a hedge backwards, as if he had no agency in the process.

I mention her appearance, by the way, not to body-shame but because Kaufman’s deliberately cast some of the most beautiful people in Hollywood, circa 1999 – Diaz & Cusack – and made them look ludicrous to explore the disconnect between mind & body, sex & gender, as if there’s a beautiful soul, fit to be a star, hidden inside every crude vessel, if only all the shallow people in the world could get past their appearance. Isn’t that our shared fear-slash-fantasy? That we’re just ugly ducklings who’ll metamorphose someday, whether cis or trans…? Malkovich embodies the opposite: the archetypally weird-looking actor who somehow transcends character-actor status through sheer force of talent and charisma, giving us all hope that we can be loved and admired and successful without being conventionally beautiful; he also transcends the fourth wall, appearing under his own name, but more of that later.

When Craig tells Lotte “It’s just a phase” (her desire for SRS), she replies with a wounded “Don’t stand in the way of my actualization as a man,” an uncannily resonant piece of dialogue 25 years on because while all 50 million trans people on the planet right now have probably heard the former countless times in their lives (if only in their own heads, if they haven’t yet told another soul), her response is the kind of therapy-speak you rarely heard before the 90s and any laughter it elicited then, or now, is invariably awkward: for her it’s deadly serious, a matter of life and death (whether spiritual and literal), and yet her callous husband – the one person who should know her best and most want happiness for her – is being patronizing, as if she’s a stroppy teen.

As a cynical Brit in the 90s, this kind of thing was uncomfortably East Coast American, and it’s taken until my mid-40s, after a few years of good therapy (after a couple of decades of sporadic and often very bad therapy) to see the value and precision of terms like actualization, validation, authentic-self, presenting-as-me (rather than, say, “cross-dressing”), and Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy (rather than the perfectly clear but less accurate Hormone Replacement Therapy). If Lotte couldn’t “actualize” masculinity, s/he’d just be a lonely puppeteer, using an artificial intermediary – a half-hearted performance of femininity – to interact with others, without truly being seen, or touched, or understood, let alone loved, whatever that means. Kaufman was ahead of his time with his portrayal of Lotte, although the film wouldn’t be half as smart if it hadn’t already set up Craig as her double, the epitome of what I’ll call “Cis Gender Dysphoria”. Just 24 minutes into the film, Craig uses puppet-Craig and puppet-Maxine to imagine his seduction of the latter:

P-M: Why do you like being a puppeteer?

P-C: Well, perhaps it’s the idea of being inside someone else for a while. Being inside another skin. Moving differently, feeling differently.

P-M: Would you like to be inside my skin? Think what I think? Feel what I feel?

P-C: More than anything.

P-M: It’s good in here, Craig. Better than anything. Better than your wildest dreams.

The double coding here is perfectly balanced: Craig wants to believe he’s saying something terribly profound and Existentialist about transcending the limits of subjectivity and in his fantasy he’s rewarded for his intellectual and artistic prowess with sex (getting inside her skin); at the same time, he betrays a pseudo-transsexual desire for feminine subjectivity: to know whether the Sexual Other truly possesses all he lacks, as a man. Speaking as a trans woman who’s done a lot of hard thinking – by which I mean the kind of thinking you do to keep yourself alive, in lieu of hormonal and social transition, rather than trying-to-fathom-what-Jean-Baudrillard-or-Judith-Butler-are-on-about, which is my kind of fun – I can assure you that the Other really isn’t Other, just different in emphasis on various behaviours and emotional intensities, and what you get from transition isn’t unlimited happiness but the chance to be your Better Self (as you remember it, pre-transition) more often, and for longer, so long as you work hard at it, without plummeting into inexplicable despair no matter how hard you try, because – Sorry – you never had the right hormones and that performance you were putting on…? Well, you weren’t bad at it, no-one ever guessed, sometimes you were pretty good and you attracted attractive people who made you feel better about yourself but – God! – it took so much effort, so much brain-space monitoring your every move for tells, when you could have used that RAM for pretty much anything else. Such is (Trans) Gender Dysphoria.

The whole business about “skin” here is very loaded. Only seven years before Malkovich, The Silence of the Lambs (1992) was one of the most critically acclaimed, Oscar nominated films of the decade, and its parent novel from 1988 was similarly lauded; there, the “false-transsexual” (as Dr Lecter diagnoses the killer) was attempting to construct a “skin-suit” from dead women, having been turned down for SRS, since his desire was the result of horrific abuse in childhood rather than innate trans identity. Kaufman, I suspect, was conscious of this, although if nothing else he’s playing on the idea that “skin” in American slang is metonymic of sex, as a counterpoint to the more cerebral reading Craig claims: that he’s interested in the nature of identity. [[1]] Throughout, Craig is obsessed with overcoming the barriers to fulfilment without Doing the Work (in the psychotherapeutic sense or the literal one) hence the appeal of a portal to the imagined Other realm where he’ll find celebrity, desirability, immortality, and limitless pleasure, without ever venturing inwards and questioning his own warped values, which are certainly bigger barriers to fulfilment. This is what I call Cis Gender Dysphoria: the deep distress that ones performance of gender and/or innate physical traits are inadequate, without the “Trans component” that is a need to express a different gender, with or without a need for different hormones, and various surgeries.

The questions raised by Craig’s character for trans and cis viewers alike are unsettling: for all our intellectualization of our desires and needs, for all our attempts to “self-actualize” through our Art (the apex of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs) does it all just boil down to sex?! For a trans person, compelled to analyse every desire for possibly psychopathological traits (because we were still regarded as intrinsically disordered until 2013), this question was haunting and may still be, in the 2020s, for those of us who haven’t yet found a good enough therapist, confided in enough good friends, or read some decent psychoanalytic literature. As a closeted trans woman in academia at the turn of the 20th century I was in the right place at the wrong time to discover the notorious “Autogynephilia” Theory of Trans Identity: that we transition so as to embody the target of our sexual desires. Ray Blanchard was debunked years ago but damaged a generation by convincing enough trans people and many of the medical gatekeepers they might have encountered that It’s All Just a Kink. Which it is: it just happens to be Blanchard’s kink, not ours.

Around 58:00, Malkovich gets seriously disturbing. Craig’s already learned that Maxine likes the combination of male body and feminine longing but since he’s so invested in the idea of himself as an artist who deserves love (by which he means sex and power, since he can’t distinguish these things) he threatens his own wife at gunpoint to arrange a date between Maxine and Malkovich so he can enter the latter’s portal and seduce the former. It’s possible to get distracted by the intricacy of the metafictive conceit, or the surrealism, but let’s be clear: he literally cages his wife, metaphorically abducts a stranger, and arguably rapes Maxine, having sex with her under false pretences. If we ever thought Craig was sympathetic – which we might well have done because it’s puppy-eyed John Cusack, styled exactly like literary heavyweight du jour David Foster Wallace [[2]] – this is where we have to realize he never was in love and even his overwhelming sexual desire (which we sometimes try to excuse as a force beyond our control) may disguise something uglier: the Will to (Over) Power since Maxine repeatedly emasculates him, scene after scene, from the first interaction when she sneers at his feeble attempt at seduction disguised as wit, to her mockery of him as “…someone I could never be interested in: You play with dolls” in the scene that’s jump-cut from his puppet-fantasy (quoted above), to the withering putdown when both he and Lottie try to kiss her, and she simultaneously implies he’s not enough of a man OR a woman, and she needs both (i.e. Lotte in Malkovich).

The running joke that Malkovich (the character) is most famous for being in “…that film about the jewel thief” points to this as a conscious theme on Kaufman’s part: for the psychically immature man-child, whom we now call an InCel, attractive women are harridans who thieve men’s “jewels”, symbolically castrating them; frumpy women who’ve gone to seed are jewel thieves because they, too, deny them satisfaction; celebrities are jewel thieves because, by being more attractive, they make beta-males feel like cucks.

(God! I’m glad to be rid of my testosterone! You can be the nicest of Nice Guys; read all the Kristeva Irigaray Klein Butler Cixous Lorde hooks Whoever; tell yourself you must have been chosen for a reason by those super-smart women with the multiple degrees, and all their feminist literature that you borrowed to Really Understand Them… and yet you still beat yourself up when someone flirts with them because you wish you could dress the way they do & be desired the way they do, or want to beat that person up, which then makes you want to beat yourself up, and at peak dysphoria sometimes you do, and finally you know you’re the broken person the DSM-V says you are… and all of popular culture besides. You deserve this pain. You don’t deserve the gender you want. You’re exactly the monster they say you are. It can take a LOT of therapy, and hormones, and Real Life Experience Presenting as Yourself, to start to un-ravel this. Some people don’t make it.)

The final third of the film is even more grim, only slightly relieved by more inventive surrealism and black humour than the first two-thirds. Craig, puppeting Malkovich, is more successful at pleasing Maxine sexually, trashing our illusion (as viewers) that she might have more of a moral compass than him because she’s a woman who doesn’t use a gun to get what she wants, and Craig also manages to puppet Malkovich toward greater fame and fortune (although as Maxine puts it: “…if Craig can puppet Malkovich, and I can puppet Craig…”). There’s a subplot about using the portal to gain immortality for a group of characters who are obviously eccentric but moderately more benign. There’s Malkovich’s unforgettable trip through his own portal I’ve written about elsewhere although it’s NSFW, for now. Maxine’s character arc becomes more interesting when she realizes that she has maternal yearnings, like Lotte, although the overarching trope of puppetry makes us wonder whether this is a “truer” kind of love or just a way in which we’re puppeted by our instincts: the Dawkinsian “Selfish Gene.” The film is semi-optimistic about the possibility of true love between women, and/or between women and their children (after initially suggesting that such love would require the heternormative pattern of one partner behaving like a man) but it’s much more sceptical about cis men and their desires. The few who achieve some kind of happiness are conspicuously wealthy, elderly, cis-het, and white. Do they achieve love, though…?

In my early-20s, I couldn’t be sure about any of the implications. 25 years later, I’ve found some of my own provisional answers to problems that haunted me, although I still can’t say what Kaufman conveys about masculinity, whether or not he intended it; his contemporaneous notes in a Faber edition of the screenplay spoke about his utter despair at the time, and a complex relationship with his elderly mother. I’m not going to Google for clues his “egg has cracked” (just yet) because it wouldn’t answer anything about the film itself. What I learned as a new parent (pre-transition), is that ones feeling for ones infant-child can be so powerful it’s an almost magnetic force, pulling you toward them, compelling you to protect them, and cherish them, and convey through your body language that they’re loved, no matter how walking-into-doors-tired you are… but all of this could be a biological mechanism perpetuating the species because, God knows, it’s not like there’s a personality in there yet, just an image of yourself blended with your partner. That experience meshes with the cynical reading of the film’s ending that it’s hard to entirely escape.

What I now know, as a trans parent if not a trans mother (post-transition), is that ones feeling for the personalities developing and complexifying and enriching themselves in front of me – seeing the world and all its phenomena for the first time and in the process enabling me to see them anew, to see them through their eyes with all the associated joy, unmuddied by adult cynicism – might be one of the best feelings one can have as a human being. There’s no sexual component, no Will to Power, and, even if I’m kidding myself and the Selfish Gene is more ingenious than I can imagine by offering Parental Euphoria as a reward for procreation, I’ll take it.

I don’t think Kaufman was wrong to make Phallic, Narcissistic, Masculine Rage the antagonist of his film, with few rounded male characters, nor to present the various feminine strategies to negotiate such rage, which are often sadly necessary given the asymmetry of male & female anatomy but potentially abused; I just think we need to look to his work ten years later, in Synecdoche NY (as we’ll do next week) and Antkind, ten years after that, where his larger cast and larger canvas allows him to start to redeem men and women and trans people however they express their gender from a bleak worldview in which we’re all Dysphoric.

[1] On a tangent, Celebrity Skin was one of the more successful soft-porn magazines of the decade, and the Hole album of the same name, released in 1998, uses the line “I want you under my skin” to play on the idea of heroin addiction as a substitute or remedy for failed relationships (in Courtney Love’s case: with her negligent parents, and her late-husband, the most famous heroin addict and suicide of the decade, very likely a trans woman afraid of transition). We see skin more than anything else of a person, we fixate on it, we find different ways to try to puncture it, and sometimes literally puncture it as if that’s the answer, but the hardest thing can be to communicate with the person on the other side of it, if we’re incapable of ignoring it.

[2] I could easily write another essay, almost as long, arguing for Malkovich as a partial cinematic adaptation of Wallace’s collected fictional works, up to 1999. Puppets appear as a way of defamiliarizing the author-character relationship in Wallace’s Infinite Jest (1996); transsexuals and transvestites are (rather cruelly) used as symbols of clumsy authorial avatars or “travesties” of the Real in more than one novel; Cusack is styled like not one but three incarnations of Wallace; Wallace had publicly confessed that his most famous novel, for all its erudition and logorrhoea, was a failed attempt to seduce one of the most talented female writers of his generation. It’s plausible Kaufman had heard some of the rumours, corroborated by a biographer after Wallace’s suicide, that he was violently abusive to more than one ex- despite his Ultra Nice Guy persona. Playing Devil’s Advocate, the psychical pain felt by Craig at the end of the film seems a lot like the pain Wallace was allegorizing right to the end of his own life, just 46, never having escaped the hold of what he called Actaeonizingly Beautiful women on his psyche, and for all that he did wrong I wish he could have found a chemical remedy, and a therapeutic one, as effective as I have, for all he did right.