Cis-Phoria: The Substance (2024), dir. Coralie Fargeat

Unlike so many films we want to see as trans allegories, The Substance actually is about cisgender dysphoria and might just be an aid to empathy both ways.

Cis dysphoria. It won’t come as a surprise to trans readers that it exists, and underpins many of our strongest arguments about the injustice of so-called “trans healthcare” in many countries, where the same drugs and procedures are available to cis people for almost identical conditions with waiting lists an order of magnitude shorter and without many of the humiliating gatekeeping procedures trans people face.

For many cis readers, it might feel uncomfortable to consider a facelift, breast-enhancement, or hair transplant as being motivated by a kind of gender dysphoria (i.e. distress-at-not-feeling-you-meet-the-standards-of-your-Assigned-Gender-at-Birth rather than feeling-distress-at-the-gender-to-which-you-were-assigned, which is different but so obviously analogous that there’s no justification for such radical difference in treatment). Okay, you might say, but isn’t Gender Dysphoria the main criterion for being trans? No, that’s out of date but you’d be forgiven for thinking it is, given how long it was regarded thus; the main criterion now is a persistent sense of Gender Incongruence: not matching your AGAB, with or without distress, which means that many cis people can actually have GD worse than some many trans people, and we need to spend a little more time thinking about why that is.

But this isn’t going to be a piece about institutional transphobia in medicine and the absurd diagnostic criteria of the past; I just want to put it out there that cis dysphoria exists, before exploring why that matters and some of the moral questions it raises.

One of this year’s most acclaimed films, and obvious Oscar-bait for its older actors, The Substance isn’t a trans allegory, per se, but it’s going to provoke mixed feelings for trans viewers and there’s the hope that we (trans peeps) might gain a little empathy if the film is framed as a representation of dysphoria (as a cis and trans phenomenon, as well as a male and female one) rather than narrowly interpreted as a dark fable about the psychical cost of ageing, especially (but not exclusively) for women.

Briefly, The Substance charts the fall and rise and fall of Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), whom we first encounter as the presenter of a fitness programme aimed at the over-50s. Even before we see any characters, we’ve seen her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame set into the pavement, formally unveiled, gradually weathered, and literally start to crack, in the opening montage. Everything that will happen in the story is ruthlessly pre-determined, it’s implied through such a long montage, but the use of foreshadowing in this and several other scenes is done with considerable nuance, priming the viewer to anticipate the normal human ageing process with the opening one and, later on, to anticipate self-mutilation, cannibalism, violence, and numerous forms of ever-escalating body horror, through grotesque shots of abject matter in almost every scene that constantly collapse any imagined difference between the human (as ensouled being) and the animal, vegetable, or mineral (as matter to be consumed, digested, and excreted).

The first scene, proper, after the opening montage, is a fitness routine that reeks of desperation and sets up the plot with all the directness of a fairytale; yes, Sparkle looks great for her age (damning words!) and appeals to a certain demographic but it’s only a matter of time before the network replaces her with a younger model. In the second scene, Sparkle has to use a stall in the Men’s Room because the Ladies is Out of Order hence she overhears a phone conversation from the appalling Network boss, Harvey (Randy Quaid) who wants to get rid of her, on her birthday of all days. This is where we get our first visual surprise and it’s hard not to see this as Quaid’s award-ceremony-clip: thrusting his face close to the camera as he implicitly urinates off-camera (or, we might imagine, into the faces of viewers in the Stalls), so we see every last wrinkle, liver-spot, and broken-vein, as he gurns furiously, his skin tinted almost magenta to resemble a turkey’s wattle and snood. This shot sets the tone for many that follow as it becomes clear that Coralie Fargeat, the writer-director, wants to not only critique the male gaze but also subject it to a female gaze in which the vast majority of men are pathetic creeps or, occasionally, bubble-headed male bimbos who don’t (intriguingly) present much of a physical threat (bar a couple of tense moments) just a psychical one as they bolster or undermine female self-esteem which seems to depend as much, if not slightly more, on seeing oneself as conforming to the Hollywood Ideal. It’s an interesting and, I think, important artistic decision to make the men almost cartoonishly insipid (almost like caricatures by George Crumb or Daniel Clowes) and while it might be misinterpreted as getting Men off the hook, she gestures toward other ideas she might have explored so as to make it clear what she consciously chose to bring into focus, being bored of male violence as a theme but certainly not in denial.

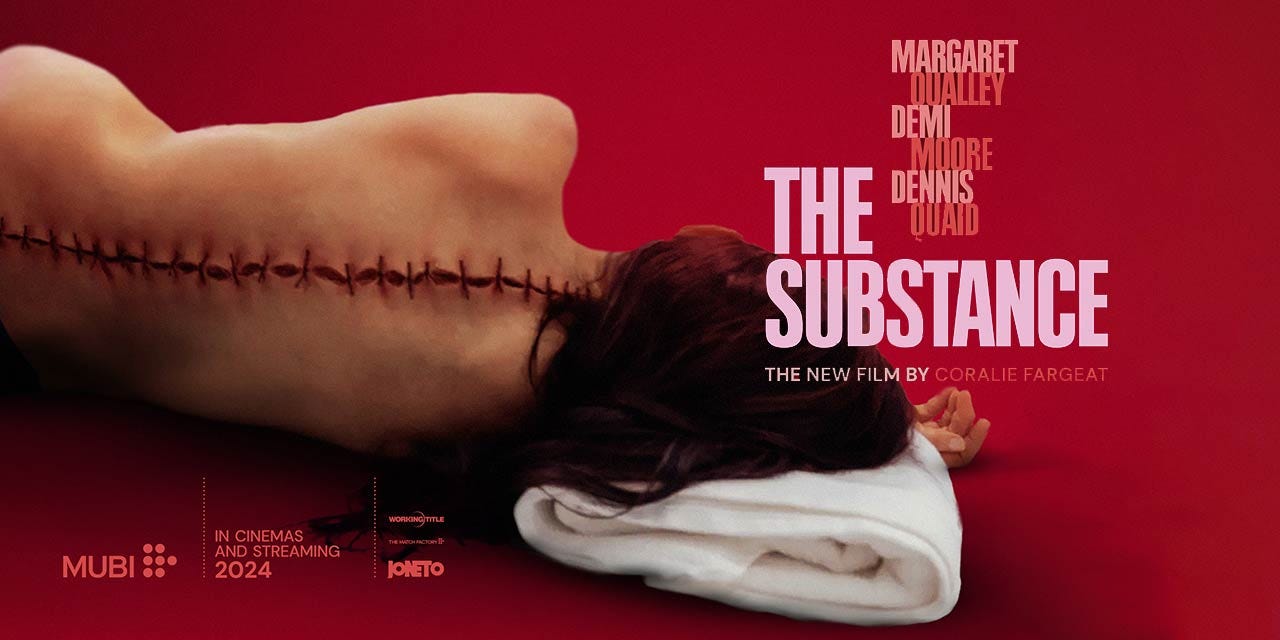

Harvey’s name, for instance, screams “Harvey Weinstein” (and all his atrocities, and the #MeToo and “Balance Ton Porc” movements) prompting us to consider how much male privilege enables sexual assault and predation, and spend a large portion of the film anticipating both, without any such assault ever happening. Now, that’s power. The black hole at the centre of this galaxy of associated ideas. Meanwhile, we might have expected competition between multiple women to be depicted, representing a range of body types, ethnicities, classes, ages, and attitudes to ones body but, No, the central dynamic is between Sparkle and her Other Self, “Sue” (Margaret Qualley), who stands (in the simplest possible interpretation) for the beauty of her younger self haunting the ageing star precisely because she’s been ejected from her own body by taking the eponymous Substance. The virtue of the allegory is that it signifies the narcissism and intense loneliness of this predicament: there simply is no-one else involved, or no other person is as much a threat when one is this self-absorbed. In other words, it’s one thing for an insecure woman to struggle with the Queen Bees of her social world (as in Mean Girls, Legally Blonde, and innumerable other comedies), which can also be presented as horror (as in Black Swan, which is stylistically and conceptually closer to the present film) but the parthenogenetic production of Sparkle’s nemesis, bursting out of her own back like a giant vulva, foregrounds the concept of internalized misogyny; she’s her own worst enemy and that’s partly how the Patriarchy succeeds: by making women do Its dirty work for It and, like the Devil in the proverb, convincing the world It doesn’t exist.

On a tangent from feminist and trans themes, I want to reiterate just how much the camera’s eye lingers over abject matter, and reminds us we’re just a bunch of bone machines / meat puppets / viruses with shoes / animate dirt with pretentions to having purpose and meaning. The prawn wiggled close to the camera in an early scene (like a flaccid member) might be a bit on the nose, as is the fly in the wineglass, but there’s a craftsmanship to making even the ketchup clinging to the inside neck of a bottle look revolting, as just one among dozens of examples of everyday horror, in the early scenes we wince at before the pus and ulcers and prosthetics start metastasising onscreen, and then it all goes Carrie / Akira / The Elephant Man / Alien 4 / vintage Hammer horror simultaneously in the stylistic overkill of the climax. I’ve said before that The Matrix feels less, to me, like a trans allegory than an allegory of late-capitalism (despite being the kind of transfem who has to make a daily resolution to stop harping on about this stuff); likewise, there’s a reading of The Substance as one long propaganda film to make a hypocritical pescetarian like me just go full Vegan or convert to Jainism. In the fourth act (as it were), a close-up on sausages frying was so stomach-churning it made me feel that I’d committed both child abuse and animal abuse by serving my own children the same only a couple of hours before. It also, rather brilliantly, led the viewer to anticipate that the increasingly mad ageing star might decide to butcher and cook her younger self (which, SPOILER, she doesn’t) in a narratively brilliant feat of having-ones-cake-and-eating-it. Yes, Sparkle is a fly in a wineglass and mincemeat being put through the industry grinder and various other visual metaphors but she – and we, the viewers – are also just meat, and food for maggots. The Naked Lunch – Burroughs’ figure of speech for the brutal reality before us as well as the Cronenberg film of his novel – are conceptual and stylistic influences here, especially when Sparkle morphs into something very Cronenbergian at the end, with her hunchback and protruding vertebrae. From a very simple premise – a French feminist Portrait of Dorian Gray relocated to Hollywood – springs a multifaceted critique of the human condition.

So, here’s where I ask a different question to my usual ones.

Not, “how might this work as a trans allegory?” or “why do we trans people fixate on body horror?” (duh) but “why do we (humans) keep coming back to Faustian pacts where relatable, potentially redeemable characters are so comprehensively destroyed?” One moral to this film is: “live by your looks, die by your looks” and that’s perfectly valid but, seriously, why do we put ourselves through this? I could have seen Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, and enjoyed the feeling of passing through my second puberty and being able to identify with goth femmes without a trace of gender envy – hurrah for oestrogen! – which would have made for a very different SubStack. Instead, I put myself in the position to ask: what was I really signing up for when I started ingesting The Substance that changed my life, just over two years ago? (No, I don’t inject my potions of choice, although the film plays on the iconography of shooting up to slam home the idea of Beauty, especially Femininity, being destructively addictive.) This could still destroy me; could still unravel my career and, in turn, my ability to provide for my family. I could still become something like the psychopathic crone that Elizabeth Sparkle does in the fourth act, before she becomes an Akira / Elephant Man monster in the fifth act: more demented than dangerous.

I’ve often told myself I transitioned to stay alive, for the sake of my children, whom I might not literally deprive of a second living parent (because of the cruelty to them) but whom I already felt I was depriving of a parent who was fully alive and hence as present and loving as they could have been. But. But-but-but…didn’t I also want to be seen, desired, and wanted as a woman? Am I going to be punished for such hubris – not in the common sense of “pride” but the stricter etymology, implying something more like wanting-to-be-a-hybrid-of-human-and-god, a man/woman transcending gender and escaping biological destiny…?

On reflection: No, I’ll stick with that first reason as the more prominent one, with the others barely a consideration three years ago when I set this process in motion, delightful though it has been to experience all of those things (being desired, yes – but also treated, befriended, respected – as a woman) in the past year, slow process that it is. But, having watched The Substance, I’ll be vigilant about succumbing to those other temptations to spend more on clothes, make-up, and perhaps even surgeries, if I can’t get enough out of finally being my femme-self. Five hours after I left the cinema I’m still thinking about how effectively it ripped my heart out of my chest, placed it in the scales, or the crucible, or whatever metaphoric apparatus you prefer, and asked me if I can consider myself more than just the result of biochemical processes. One of the strangest aspects of being trans, existentially speaking, is that hormonal transition makes it acutely clear how much your mood(s) and attitude(s) to life were determined by very simple chemicals, beforehand, to the extent that the wrong (or less suitable) ones can make life seem worthless and the right ones can make you feel new and reborn and spiritually awakened, in a sense you’ll unironically liken to that of Born Again Christians. The Substance doesn’t make a strong argument for a soul, or a purpose, but it does have a Lynchian final shot (I’ll let you mull over) that hints at the possibility of transcendence, rather than pain and then oblivion as punishment for hubris.

True, it’s tough to watch to the extent that I don’t recall any film that’s made me wince quite so much, and I’d steer my more vulnerable trans siblings away from it, if dysphoria is still a daily struggle, just as I’d worry about it radicalizing future InCels because it can feel like men come in for a bit of a kicking with not one sympathetic figure. I can imagine a lot of viewers – male and female – walking out and debating whether the fight between Older and Younger Self was too long, too violent, too eagerly relished by the latter, and by the Camera’s Eye (standing in for what? Male gaze? Female gaze? Our worst, primal instincts?). But I’m glad it exists. It made me question whether I can justify my existence, and how I can continue to do so. Ultimately, I hope this promotes empathy among cis people for trans – recognizing our common experience of dysphoria but our far from common ability to access treatment – and also promotes empathy from trans people for cis, rather than treating us as two embattled camps.