Harry Josephine Giles: Trans Poet Laureate

A review of Them! & Deep Wheel Orcadia with some thoughts on trans poetics

While it’s easy to make a case for Dr Harry Josephine Giles (to give them their full title) as the finest trans poet working in the English language (and related dialects) there’s something so instantly damning about that qualifier, it’d be better to say “…one of the finest living poets who also happens to be trans.” Giles was the 2009 BBC Scotland slam poetry champion, has been shortlisted for various prizes, including the Forward Prize for Best First Collection for Tonguit (Freight Books, 2015) and the Saltire Poetry Book of the Year for The Games (Out-Spoken, 2018), and won the Arthur C. Clarke prize for science-fiction for Deep Wheel Orcadia: A Novel (Picador, 2021). Sections of their long series Abolish the Police (one poem posted each week throughout 2019) appeared in The Games as well as the anthology of Scottish LGBTI+ writing, We Were Always Here (404 Ink, 2019), and We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics (Nightboat, 2020).

But this is not going to be an attempt to define, explain, or explore trans poetics.

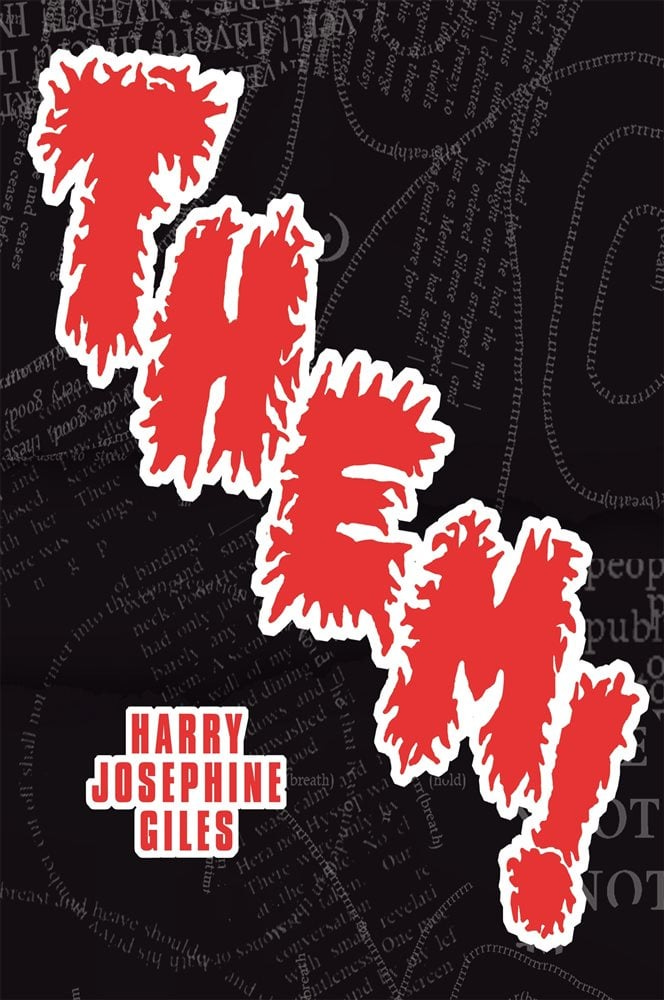

Rather, this is going to be a reflection on Giles’ newest collection, Them! (Picador, 2024) and how it plays with trans identity, the idea there might be such a thing as “transtextuality” (analogous to previous claims for homotextuality, écriture feminine, etc.), and how it ridicules the project of attempting to define either, while opening out its themes and textual strategies to a much farther reaching commentary on life in post-industrial, late-capitalist society, with extractivism threatening the very habitability of our planet at a time when trans people are often used as a distraction from the failure of neoliberalism to serve the many, and the fact that it harms us all, by pretending to “defend women and children.”

The latter point is my personal hobbyhorse but explicit in more than one poem by Giles, and it’s easy to treat it as the subtext of many, especially if being trans has made you paranoid.

The logical place to start is with the title-poem, “Them!” (pp. 10-15) which is simultaneously the most lucid and accessible, and the one that would seem to announce an overarching project to define transness and trans poetics were it not positioned immediately after eight poems that ridicule such a project by taking as their titles “Gender,” “Sex,” “Transsexual,” etc. and that are laid out in blocks of prose resembling encyclopaedia entries, only to then have a content so entirely unrelated (or related at astronomical distances) that one can derive no clear sense of the actual terms (nor Giles’ view of them) other than that they want, very much, for people to stop trying to constrain the identities of trans people whose subjective experiences may be utterly alien to them. Take, for instance, ‘QUEER. If given Nectar, Thanatos will give you the Pierced Butterfly. And the memory of it is painful to me. The green fields…’ [p. 5] or ‘GENDER. This is a very small purple flower. It only grows in Orkney…’ [p. 2] To be fair, Giles also implies that the things signified – which are also “Us,” “Me,” and “You” (my trans siblings) – might be pretty, magical, and generally weird, all of which are valid descriptors I’m happy to accept. But, first, let’s look at “Them!”:

They swallowed a small white pill and settled to write a poem.

The sun has risen an hour earlier, behind clouds.

A sentence is a subject, a verb and their ornaments.

They planned for the poem to narrate the emergence, in their

body of work, of poems identifiable as trans poems, that is,

poems which narrate the emergence, in their body, of sex.

To narrate sex is to perform a disclosure: to open a door.

So far, so lucid, and pseudo-prosaic with all its connotations of simplicity and directness. Nonetheless, the poem is a poem, formally speaking, because it uses lineation to control structure, pacing, and pausing, and because it’s ‘language charged with meaning’ as in Ezra Pound’s classic definition, which we might take to mean freighted with a greater density of images (operating as symbols pointing toward multiple possible meanings) than ordinary prose, or with symbolic situations that might suggest analogies to other processes by which individuals engage with Ideological State Apparatuses, or are constrained by them (not, itself a universal preoccupation of poetry but a common one for the avant-garde, and frequently apparent in much of Giles’ work). Without actually being verse (i.e. metrical rhyme), the poem has a pleasing, comforting rhythm with its semi-regular ebb and flow between short and long sentences, declarative statements that fall into a loose sequence pertaining to:

· the actions and immediate situation of the author

· the natural environment

· the nature of poetic discourse

· the more specific nature of trans discourse

· the role & intentions of the reader

And yet none of this is limiting or prescriptive, as the poem strains at its own self-imposed structure. At first, the poem feels like a gift to those readers who might specifically have hoped for such definitions, whether to make sense of their incongruence or dysphoria (if trans), or that of someone for whom they care (if cis or trans), or the ugliness of discourse in the Press and government (if either), or (deep breath…) the extremely niche discourse around trans poetics that serves to establish it as worthy of scholarly study and, by extension, hails trans people as autonomous creators, participating in a form of culture still celebrated as highbrow (and hence a passport to work in academia, should their collection be published) despite the longstanding efforts of many poets since the advent of Baudelaire’s modernisme to dismantle cultural hierarchies, whether of forms deemed more or less sophisticated, or the entire cultural matrices of various peoples as a metonym or proxy for their identity. This last aspect of trans poetry, and its ideological contradictions – the critique of hierarchies that simultaneously maintains or instantiates hierarchies – is alluded to in an early pair of stanzas:

A book which has a sufficient quantity of trans poems is a trans book, a book which

gains access to and is excluded from certain forms of literary attention.

A book which has content of strong significance to trans communities is eligible for the

trans literary prize, while a book which is written by a woman is eligible for the

women’s literary prize; both, however, must be written in English.

The poem as a whole is meta-poetic but here Giles is at their most personally reflexive, knowing the reader may be inclined to judge how much this is “a trans book” (very) and the paradox that this simultaneously increases the likelihood of certain plaudits while decreasing the likelihood of appealing to a general readership; Giles knows they are good, if not great, by one metric – and almost insignificant by another – and such is the predicament of all trans people, by analogy: heroically navigating a bureaucratic labyrinth that cis people might struggle to imagine…often for the sake of achieving invisibility, or “illegibility” in a sense explored later in the poem.

The second stanza of the pair above plays with the common fallacy of an opposition between being trans and being a woman, without explicitly affirming the opposition or refusing it (e.g. by asserting “trans women are women / trans men are men”) and, instead, comments on the fact that neither kind of prize is truly inclusive since both may exclude people from other cultures. Yes, trans people are more likely to advocate intersectionality (partly because we need to be part of a broad coalition so as to survive) than the demographic that creates, adjudicates, and consumes the winners of ‘women’s literary prize[s]’ but neither “side” has a monopoly on ideological purity.

As a preliminary to developing a trans poetics, Giles deploys an extended metaphor wherein the general act of writing a poem is analogous to ‘…open[ing] a door’ (alluding to long-standing discourse about poems that are more or less “open” or “closed”) although the more specific instance here is the writing of a poem that ‘…narrate[s] sex…’ and ‘…perform[s] disclosure…’ where the latter term is a pedantic, trans-specific synonym of “coming out” that erases certain traditional associations (i.e. with debutantes’ balls), just as the less commonly used “Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy” is a trans-specific synonym of HRT, grafting positive connotations of “affirmation” onto a term primarily applying to treatment for the menopause in cis women, so as to counteract the historic pathologization of trans people.

‘Perform[s]’ is, itself, a loaded term, evoking Judith Butler’s theories about gender. However, nothing is simple about ‘…narrat[ing] sex…’ as Giles is making the bold assertion that sex is something that can be narrated and performed, not just gender, as is more commonly accepted. Regardless of gender presentation, most trans men and women in the UK legally retain the sex they were assigned at birth (due to the bureaucratic labyrinth), and yet the Law is out of step with Science which often seems to point toward the conclusion that to be “trans female” or “trans male” (which are not terms in common use) would entail belonging to a distinct sex, which might be defined as “those people whose brains function optimally on hormones not ordinarily produced by their bodies, or sub-optimally without them.” That said, this inference is at odds with the dominant trend in political thinking on trans issues, where “transmedicalism” is reviled by many who wish to remain under “the trans umbrella” whether or not they need or (yet) take HRT / GAHT. Later in the poem, Giles draws attention to the act of taking medication, and hence altering ones body and neurochemistry, sidestepping debates about the validity of non-binary people who do not seek hormonal transition or trans people pre-HRT , but sets up a puzzle for the reader by mentioning the E & T levels of the subject who could be a trans woman seeking to lower her T further or a trans man seeking to raise her T (and so on) but is, in any case, on a threshold. The poem is, as promised, about the ‘emergence of sex’ but refuses complete disclosure, perhaps because of the risk engendered.

This is also what I mean by ‘…language charged with meaning…’ whatever else Pound may have meant.

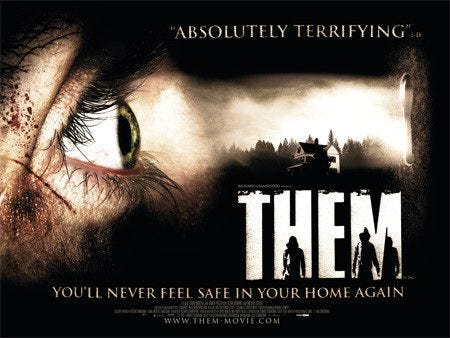

The apparent neutrality and universality of the door (lending itself to ideas of concealment, division, separation, transition, etc.) suggests that Giles is trying to avoid the obscurantism with which avant-garde poetries are so often charged… except the poem demonstrates there is no such thing as a discourse exempt from ideology or poetry. There are little dashes of wit in a phrase as simple as ‘Many things may come through that door,’ which we’re primed to read as supernatural beings, the stuff of Horror, or abject ones reviled by dominant groups, since the cover of the book spells out THEM! in a font resembling splattered blood. Bear in mind, the poem isn’t blandly titled “Them” but “Them!” evoking horror films like They Live! (1988), The Thing (1982, 2011) or Ils AKA Them (2006), as well as eliciting the range of violent emotions when trans & non-binary people appear in popular discourse.

In the days after Trump’s re-election, the word has accreted an additional, grubbier layer of significance since many Democrats are currently blaming their party’s failure on “woke discourse” that cursory media analysis will tell you they avoided like the plague; if anything, more wont to ape Republicans by throwing trans people under the bus. One attack ad literally stated: ‘Kamala Harris doesn’t stand for you but for they/them.’ (See what they did there?!)

In short, the most superficially accessible poem in the collection is anything but simple.

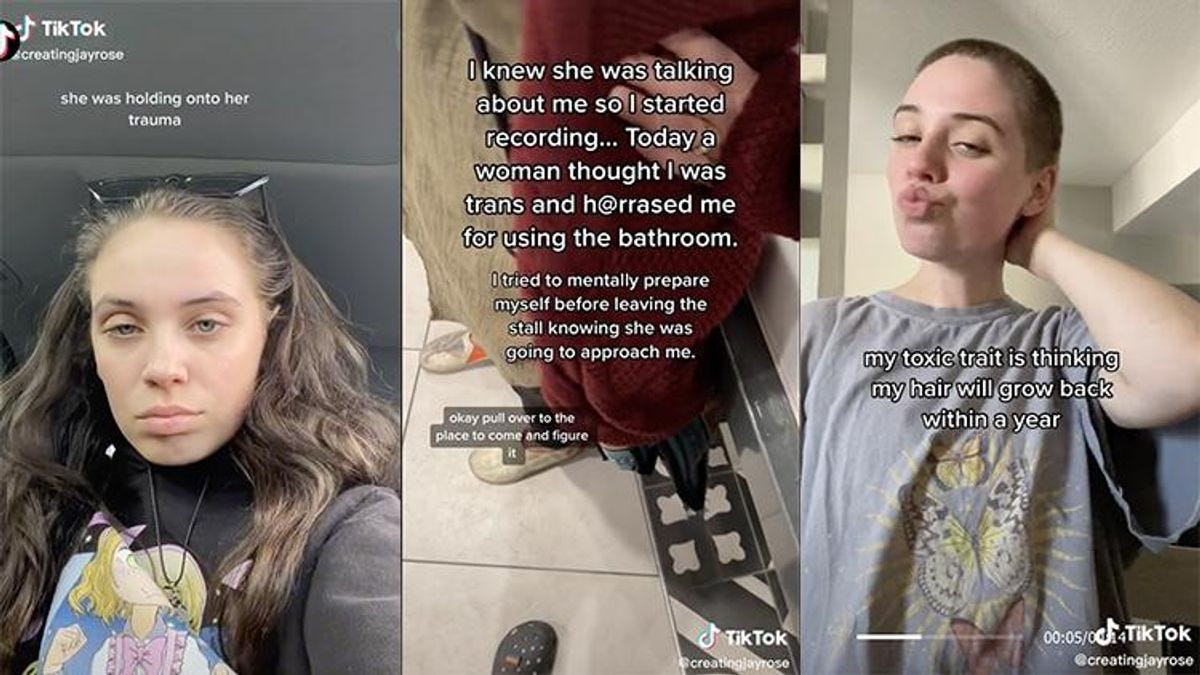

But it is playful, and one of the things that makes it so playful is the refrain that appears for the first time at the bottom of the first page: ‘You read the poem. / You want to know to which sex the poet belongs. / You can find out if you like.’ – which is hard not to read as obscene, crashing the poem sideways out of its academic framework into… what? Something more like pornography? Yes, you can find out Giles’ AGAB online (this mysterious person whose full name is Harry Josephine Giles, doesn’t have a photo in the book, and who looks androgynous in many of the pictures, until recently, in a way that might provoke “transsexual panic”). But there’s a salacious undertone here, as if reading the poem is equivalent to an erotic Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Book that enables you to reveal the author’s genitals… although this would not reveal their ‘sex’ (according to sex-critical discourse) since genitals are not the sole determinant of sex in the schema proposed above wherein trans female is distinct from cis female and so on. “Genital sex” (which is implied, here) is very much a Gender-Critical or Trans Exclusionary concept serving to denigrate trans people as potential predators and rapists (as if possession of a penis, or male levels of testosterone are automatically dangerous) under the cover of a pseudo-science that simultaneously purports to be neutral, objective, and to protect women and children but also assumes an absolute right to surveille the genitals of others. This is not only obscene in principle but has, anecdotally, resulted in more instances of cis women assaulting and harassing gender nonconforming or “mannish” cis women, than any predators being caught.

I’ve already passed 2,000 words in a piece that was supposed to be ‘a brief reflection’ and I’m one page into a six-page poem. This is what an ex- used to call “paranoid criticism.”

Multiplying the possibilities for analysis of individual stanzas, the poem operates through a system of analogies whereby the pair of stanzas about publishing and prizes (for instance) maps onto a later pair, whose connexion is marked by a parallelism, viz. ‘A body which meets a sufficient quantity of diagnostic criteria is a trans body, a body which gains access to and is excluded from certain forms of publicly-funded healthcare’ and the more stinging:

‘A woman who possesses the diagnosis of gender incongruence must be approved by a psychiatrist to be eligible for breast augmentation, while a woman who lacks such a diagnosis needs no psychiatric approval; both, however, must have sufficient funds.’ [p. 12]

These are valid points, in isolation, but the parallelisms suggest that starting medical transition can feel a lot like getting a literary prize, in terms of the difficulty involved, the achievement felt, and the sad fact that neither matters much to the larger cis readership or public. The second stanza echoes the earlier critique of prizes, making it clearer, this time, that double-standards apply to cis and trans women – we, the latter, are psychopathologized as a precondition of treatment, even after the diagnostic requirement “gender dysphoria” was replaced with the less loaded “gender incongruence” circa 2013. The violin is a little larger this time, and yet Giles still hints to her readers that they may be privileged in the global context (recall that the average UK citizen is in the global 1% for income, however hostile “TERF Island” may feel).

The fact that the poem operates through a system of analogies that the reader is encouraged to discover is foregrounded in a later stanza pointing out that ‘The adjective ‘trans’ emerged through the interaction of medical case study, literary memoir and political action: three forms of narration’ [p. 13] so, yes, the poetical is political. The disclosure of this inter-penetration of discourses is not, however, limited to trans identities and one can imagine various types of reader being unnerved by the pair of stanzas: ‘A legible sex is a sex which can be read’ and ‘To read, in trans community, is to detail the ways in which the subject fails in their performance of sex’ [p. 12] making readers wonder whether all our acts of reading other bodies may be felt by those who are read as failures; making us wonder how we are read ourselves; and whether we implicitly threaten others when we are seen to be reading them.

Giles plays with this ambiguity by leaving the possibility of violence to the reader’s imagination and evokes, instead, a sense of confusion and uncertainty that may be closer to the subjective experience of trans people in any given day, in any given interaction. When the penultimate stanza reads ‘‘Window’, ‘breasts’ and ‘literature’ are not metaphors of identity, and ‘sun’, ‘pill’ and ‘poem’ are not metaphors of sex’ [p. 15] she suggests a parallel between literary analysis and the act of trying to read a trans person, both being absurd: what are we going to do with the information that this person may or may not have had HRT, may be moving in the direction MtF or FtM, may or may not have had surgery, top, bottom, facial or elsewhere?! It’s simply not relevant most of the time, barely alters our behaviour, and yet our brains seem hardwired to detect anomalies, which may have originated as an evolutionary trait but has also, it’s reasonable to suppose, been reinforced by late-capitalist ideology as the cis-het nuclear family is deemed so integral to the reproduction of the workforce and its values.

All of which sucks the playfulness out of the poems so I’m going to zip through some others, reflecting on what I enjoy about them, while keeping in mind this can also be FUN.

Another poem vying with “Them!” for the most lucid or accessible, for its astute, self-contained political analysis, is “The Worker” [pp. 26–32]. Again, the title is ironic; once you have a sense of who the subject is, there’s something almost as grotesque about using the term as there is about referring to trans people as ‘Them!’ In this case, we get a biographical sketch of the kind of well-educated person who simultaneously agonizes about their privilege while desperately consoling themselves they might have victim status, so not everything’s their fault. We all know her and, TBH, many of Giles’ readers have either been her or will be her at some point in their / our lives. In style and content, the text so strongly recalls “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men” (the crypto-novella within the collection of the same name) by David Foster Wallace that I’d be amazed if Giles is unaware of it, even if they didn’t consciously intend to flip the gender and inscribe the subject within a more explicitly Marxist discourse that functions equally as cage or consolation. The various interview subjects in Wallace’s novella often use bastardized versions of therapy-speak, as if presuming that a performance of self-awareness excuses a multitude of sins, whether those are objectification of women, duplicitous seduction techniques, or sexual assault. The following stanza, for instance, could almost have been lifted wholesale from Wallace:

The worker at that point in the conversation launched into a familiar cycle of self-loathing, aware that her level of self-loathing and her ability to project that self-loathing onto others was itself loathsome… [p. 31]

…as could turns of phrase like ‘psychic pain,’ which certainly has been used by Wallace, to simultaneously express strong emotion and undercut it as, nonetheless, non-physical. “The Worker” is aware of her privilege in a global context, and to some extent a national one, but, knowing a smattering of political buzzwords, uses them ironically (as if that ever excused anything) to liken her situation to various forms of oppression, simultaneously dignifying her own struggle by comparing it to that of people more accurately described with such terms, whom the terms would ordinarily indicate are lacking in such dignity. Thus, it is in the penultimate stanza that we learn the worker ‘believes that her brightest times have been those when she has been able to construe her horror…as a product of ‘neoliberalism’,’ [p. 32] and what follows is a 10-line sentence that encompasses the ideology and its contradictions with a syntactical elegance that both demonstrates and performs the possession of cultural capital that is accrued by the Developed World bourgeoisie with or without conscious participation in neoliberalism or active resistance to it. This insight – itself an exercise of the same scholarship that incurred student debts without great financial reward – grants The Worker a god’s eye view of the planet (something I often hazily picture as I read such analysis, however abstract) and a god’s sense of distance from it, and consciously or unconsciously this is what enables her to finally take her clothes off the radiator, step out of the shower (both details placed in the poem to signify luxuries taken for granted in the 21st century UK…?) and get back to work…which is only in the culture industry, anyhow, despite her likening herself to blue collar workers.

At this point I feel inclined to go on a tangent to Giles’s previous work, Deep Wheel Orcadia.

Why? Because the previous ‘novel’ (as it’s subtitled, debatably) also places its subjects within a world-system (or trans world system?) that rests on extractivism, now spilling out onto other planets within the solar system, if not galaxies, since hyperspace travel has been achieved. It’s easy to read this on one level of the allegory as a portrait of life on the distant isles north of Scotland, where one is simultaneously in an environment little changed from 1,000 years ago (when Eirik the Red first travelled to Vinland, or Baffin Island) and close to the oil rigs enabling so much of modern life as we know it in 2025 (and endangering all life by 2060), with the mysterious ‘Lights’ that are a near-future source of power easier to imagine by pitcuring crude oil being burned in vast flares from platforms, than whatever Giles might have had in mind, beautiful though they’re meant to be.

Such is the setting for the novel but the point I want to make is that Giles isn’t merely imagining a future (whether as optimistic projection that we might survive, or dystopian warning of how it might look) but travelling backward and forward in time, and this happens at the level of both plot and line. That’s to say, the technicians and pilots working on Deep Wheel Orcadia are haunted by visions – more like poltergeists given the physical damage they inflict) of an ancient past due to some temporal anomaly – within the story. So far, so sci-fi. But within the Standard English translation (or strictly: crib) of the narrative that’s printed in Orkneyan dialect at the top of each page, many compound words are employed in the smaller script at the bottom that combine two, three, or four synonyms of the single Orkneyan word, such that we feel the living history of the word, writhing within it.

But noo, happan her airms aroon her nesh body sheu’s feart

sheu’s draeman yet, that whit sheu’s touchan wilno stay

==>

But now, wrapcoverbundling her arms around her softtenderhealing body she’s scared she’s dreaming still, that what she’s touching can’t stay [p. 91]

What Giles therefore enacts is a continual process of travelling through time and space and the “inner-space” of each language or culture’s web of meanings that we all to some extent perform with more or less consciousness at any given time. It’s a profoundly liberating view of consciousness and communication that we can speculate Giles might be more attuned to as a trans woman who’s spent much of her life attentive to what their own words might disclose, pre-transition, and then learning new codes as they do so, before discovering that much of their speech now has a richness that may elude the cis, whether they’re being spoken to, or overhearing.

Returning to the subject of poetics, it’s notable that the general textual strategy, and to some respect the allegory, resembles Armand Schwerner’s epic poem-cycle The Tablets (1968 – 1999), which may be the only avant-garde masterpiece to have been praised by both Stephen King and Ezra Pound, very appropriately. Schwerner was primarily a translator or Mesopotamian texts and an associate of the Ethnopoetics movement founded by Jerome Rothenberg, who frequently anthologizes Schwerner’s translations and original works alike in his innovative and influential anthologies of tribal & indigenous poetries, wherein multiple cultures are brought into symbolic dialogue. All of this is relevant. Briefly, The Tablets is a series of putative translations of ancient texts wherein the reader learns about lifeways in an early urban civilization, including its socio-economic and legal system, sexual practices, ritual worship of the gods, practices that blur the line between the aforementioned, and yet a certain amount of information is missing. From translation to translation, the reader learns that certain hieroglyphs may have multiple connotations, and therefore builds up a map of the web of meaning that makes the play of language endless and complete disclosure impossible (just as a reader of a trans text might come to see why “affirming” is so loaded or “sex” and the various terms reclaimed from slur-status such as “queer” and “transsexual”). In Schwerner’s case, one gets the ominous sense that something super- or extra-human, and super-temporal is deliberately erasing key information to conceal its existence or how exactly it intervenes in human affairs, making for a measure of humour early on and a lot of horror by the end.

I’d be amazed if Giles is unaware of the work of Schwerner but, in any case, is flipping the script, as they did with Wallace, by primarily imagining the next stage in human social & technological evolution, rather than looking primarily towards the origins of language and society.

But I say ‘primarily’ because we’re only inclined to read this as an imagining of the future because late-capitalism prioritizes a metanarrative of linear development toward greater standards of living, movement of individuals and entire populations far from their place of birth (whether permanently or to soothe chronic ennui), and the continual re-siting of primary production rather than the pursuit of sustainable economic practices (as so many ancient myths exhort us to do, by allegorizing the dire consequences if one does not). Arguably, this paradigm is a relatively recent one within our 100,000 year history, by no means normal for much of that time, and often so destructive that it requires re-setting. The ghosts that haunt Deep Wheel Orcadia are in at least one case the ghosts of ancestors who sought to plunder new worlds rather than engaging in the sustainable stewardship of old ones. I could spend much longer decoding the allegory and cross-referencing it to other political messages in Giles work (not least “Abolish the Police”) but I’d rather focus on the more appealing effect which is to suggest how liberating the imagination can be, transporting us across history and the putative boundaries of sex and gender.

In the queer love story woven through the novel, a rich kid arrives on the Deep Wheel having fled her father and reinvented herself which this particular reader is inclined to read as a transsexual allegory (since there are references to body modification in the section quote above, “Darling’s Body”) or just an actual depiction of transition. Finding love with someone else newly returned home, from a humbler background, Giles suggests the subversive power of queerness to transcend class boundaries even if she doesn’t promise the pair an easy ride. Many of the most delightful passages in the entire novel occur when the pair are negotiating their relationship, or making love, or viewing The Lights (on an early date) or dancing, because it’s here than language is at its most slippery with compound words deployed by Giles that may have three or four jammed together to translate what’s in the Orkneyan text (e.g. hintan ==> gathergleansnatching // bombazed ==> bewilderedstupefied // rax ==> stretchreachexpand // frapp ==> mixtangle). What little sex there is might be rather vanilla (by comparison with some of what appears in Them!) and there’s no high drama arising from same-sex desire to make it seem more romantic but there is a sensuous entangling, caressing, embrace of semantic possibilities that leaves this particular reader gasping for more.

Returning to Them!, Giles is often at their most playful when collapsing together times and cultures. In the title poem, it’s notable that a tarot deck is on the desk alongside the letters from healthcare providers, and “The Worker” is followed immediately by a poem that purports to be a diagram for a ritual, with a circle reading ‘salt salt salt…’ etc. surrounding a short poem that defines itself as a spell, with the aces of the Tarot suits laid out at cardinal points, although the content is more like a call to revolutionary action [p. 33]. On the following page is what purports to be ‘A scan of the ashes of the ritual in which I began hormone therapy, which I was supposed to bury in a safe [text obscured by blur that may well be ashes placed on a scanner]’ [p.34]. Facing that, a scan or photocopy of ‘A pair of bronze clamps found in the River Thames near London Bridge in 1840…’ [p. 35] which Giles implies (although the text is also obscured rather like that in many Schwerner poems) were somehow used in a ritual of her own, pertaining to facial feminization surgery, here in the 21st century, where the impulse to manifest desires in physical form survives in rituals like another one they recall from childhood involving the Pokemon Mew which is, of course, ultra-rare and trans coloured in powder pink and blue.

A few pages after that, a dinner party at a dollhouse (in the trans sense, obvs) goes horribly awry as the titular J___ C___ arrives, magically extracts ‘each drop of estrogen’ from the speaker’s body so that her ‘bones would break’ [p. 40] in a matter of years, before confirming she (J___ C___) is a ghost ‘by plunging her two hands through the pine-effect tabletop and screaming’ [p. 41] before snapping the neck of ‘Poor Hyssop’ whose ‘tits had only just come in and barely any time to enjoy them’ [ibid.]. Does it help to know that hyssop appears in the Bible as a substance used to comfort Jesus on the cross? Or that it’s a common herbal remedy? Or that trans girls favour mythical names, and dabbling in witchcraft, hence:

‘Hyssop, who had been reading a zine on contemporary witchcraft, grabbed the two-volume Library of America boxed edition of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle from my IKEA bookshelf and uttered a hex…’ [p. 40]

I can’t honestly say I understand what Giles is driving at, other than that this all feels very relatable to someone who keeps a deluxe edition of collected novels by LeGuin (famous for imagining societies with very different gender systems) on her own IKEA furniture, near the Tarot deck, and tends to suspect her cat is a familiar of its previous owner. We’re wyrd sisters, all, we nominal adults going through second puberty, as a result of a biochemical process that nonetheless compels us to perceive Time, Culture, Gender, and Identity very, very differently, often picking mythical figures and archetypes to replace our deadnames, and only embracing elements of Christianity when we can thoroughly queer them (e.g. by fixating on that hole in Christ’s pale, androgynous side).

It doesn’t matter whether Giles believes in any of the mysticism she alludes to, or sees it primarily as a catalyst for the imagination, only that it serves to evoke just how mysterious and wonderful it is that we get to do this, even if the stakes are the stuff of Tragedy and Epic, with the risk of rape, assault, and murder all increased by virtue of transition, making us kindred to the various nymphs and goddesses and humans obsessing the gods in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Not that the Greco-Roman classics are the sole provenance of allusions, and a smattering of Arthurian legend creeps in, all of it complicated by the formal strategies of concrete poetry and other avant-garde movements (hence the suite “Out of Existence” which starts at the mid-point of the book, resembling early Dada sound-poems for several voices (circa 1916–19), or Louis Zukofsky’s A (1978), which in places lays out its lyrics as if in a musical score. The broad gesture here is to assert trans poets as heirs and heiresses of all human cultures at their most ancient, most cutting-edge, most absurd, and most profound.

Elsewhere, photos of signs are cropped for the sake of weak puns or found objects [pp. 72–9], and jargon-heavy texts produced by local government at its most tedious are cut-up and resequenced, to become found poems analogous to Marcel Duchamp’s LHOOQ (La Gioconda given a moustache) or the urinal he exhibited titled “Fountain,” theoretically on behalf of Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven, generally taken to illustrate the fact that Art is in the Eye of the Beholder, produced by a simple shifting of perspective, but also a refusal of hierarchies (the enclosure of What Is Artistic within the gallery space, exluding what is outside), while incidentally appropriating the work of the “living Dada sculpture” (the oddly attired Baroness) who was one of ‘les bachiliers’ (an oft-forgotten term for transgressive masculine young women in the 1910s & 20s) Duchamp was inspired by, during his own phase of gender exploration.

Or not.

Maybe I’m just projecting as a fellow trans woman with a PhD in avant-garde poetics for whom the enjoyment is as much the free association as the actual knowing. Such is being trans: we don’t know what it’s like to be our target gender any more than we know what it’s like to be any other trans person but Giles manages to capture the fact that it’s an ongoing journey, there are always new ways to discover how human existence is inflected by gender, and if examined with an open mind - Yes - it can also just be fun.