Laurie Anderson: Last of the Renaissance Women

NOT a transvestigation but simply a case for a "trans icon" (like many a "gay icon" who happens to be cis-het) who feels like just what we need at a time of Fascism Ascendant

Laurie Anderson: Last of the Renaissance Women

(Laurie’s hair isn’t really in trans colours, unfortunately; pure chance…)

For those who don’t know her, Laurie Anderson (b. 1947) is one of our greatest living multimedia performance artists, exploring the grandest of themes – America’s role as a superpower, Humanity’s relationship to Nature, the military-industrial complex, Christian & Buddhist spirituality – sometimes using the most superficially trivial or frivolous sounding anecdotes as an entry-point, and often shifting from the ridiculous to the sublime, the whimsical to the grotesque, with a subtlety that in itself conveys a profoundly admirable attitude to problems of existence: able both to confront the horror and keep sight of the beauty while taking her audience along with her, partly due to a voice so soothing she was once cast as the Voice of God.

(allegedly Trump used “O Superman” at 2016 rallies but I can’t confirm this…)

I’m writing this on 11/11/24, a few days after the re-election of Donald Trump, when any moderately well-informed human not in a psychotic degree of denial has reason to believe the American electorate have accelerated our lemming-like rush toward a planet uninhabitable for mammalian life, with early signs of burgeoning fascism likely to include cruel restrictions on trans rights and healthcare (hence the $29 million ad-spend during his campaign), although countless groups will be targeted. After months of doomscrolling I feel temporarily numb to the implications for my siblings – or in the eye of a hurricane of emotions, yet to hit – whereas I feel a nauseated sorrow for those thousands of African-Americans who received texts, the day after the election, instructing them to report for assignment to cotton plantations. Of all the vile feats of cyber-harassment on a massive scale in the past year, this particular instance of the supposedly buried past returning to haunt the present, feels like the one most likely to be recounted in the darkest portion of a Laurie Anderson monologue, illustrating how technology is as likely to magnify the scale of our worst instincts, as it is to act as a prosthesis extending our reach to the heavens.

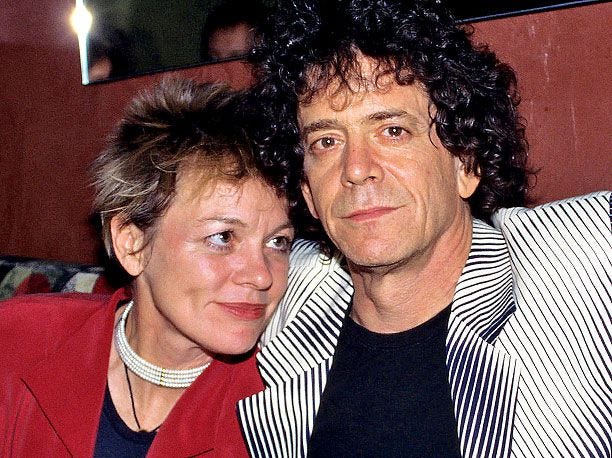

Anderson has been an outspoken critic of Trump and the GOP, for a very long time, of course, but that’s not why I want to talk about her. It’s more the fact that she (and her body of work) is such an antidote to the poisonous discourse of the present moment, and that I’ve arrived at a kind of “What Would Laurie Do?” mindset, right now, although she’s been a subtle influence on my thinking, personal philosophy, and poetics as a writer since the late-90s. Surprisingly, she’s never been hailed as a trans icon (that I’m aware of), nor said all that much on trans issues, although we can imagine her stance since she cast her old friend Anohni (FKA Antony Hegarty) as God in her most recent piece (and Elon Musk as the Antichrist), plus her late-husband was this guy – you may have heard of him…? – Lou Reed, who made an album called Transformer, back in 1973, about which I have nothing to say that the divine Ezra Furman hasn’t said far more eloquently in her 33 1/3rd book. (Laurie is also mentioned on page one of Juliet Jacques’ Trans: A Memoir (2012) for reasons that may become apparent by the end of this piece.)

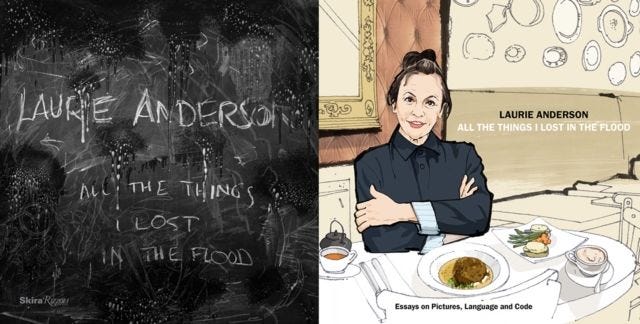

Briefly, on a personal note, it illustrates how strongly I feel about Anderson’s work that I recently had a two week binge on most of her albums and her coffee-table book All the Things I Lost in the Flood (2017), coinciding with the last days of hope for a mixed-race woman in the White House, immediately after a six month binge on the complete novels of Robertson Davies that was itself a deliberate choice to pick an author guaranteed to be uplifting and something of a spiritual guide through troubled times (individually: after separation from my partner, and “going full-time”; for the trans community, as a major scapegoat for the Far Right, after illegal immigrants; and for humanity). I returned to Anderson not by intention but by chance, which seems fitting because it’s not in her nature to thrust herself on your consciousness, and the reminder of how much she means to me was something of a gift from the universe via a friend (who forwarded an advert I would otherwise have missed), which was perfect given my long-term preference for chance to guide what I seize on next, rather than conscious, calculated intentions, which never quite work as well.

A slow drift through the works

Laurie Anderson had been a prominent multimedia artist since the late-70s but arrived in the popular consciousness via one of the more idiosyncratic singles of the early 80s, “O Superman,” championed in the UK by John Peel. Far from being a novelty single, despite its looped “ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha…” for much of its 8-minute run-time, and sprechgesang vocals put through a harmonizer, the lyrics epitomize her approach to historic events: abstracting certain elements just enough to derive a pattern we can recognize as analogous to other events in history, while retaining sufficient particulars to have an absurd or cartoonish quality. It’s not obvious it’s ‘…about the failure of the hostage rescue mission in Iran when several helicopters crashed and burned in the desert in what was meant to be a demonstration of American technology and daring’ (as she explains in the “here come the planes” subsection of …Flood) because the focus is on creating a musical expression of the naïve triumphalism that preceded the episode, and gradually hinting at a dark outcome that’s left to the listener’s imagination, as a partial consequence of the hubris foregrounded.

Similar, but arguably more powerful, is the opening track of Big Science (1982), itself a section of the epic United States performance she’d been working on since the late-70s. “From the Air” AKA “This Is Your Captain” is one of the most remarkable evocations of the age of America as a superpower of the past 50 years, which is archetypal Anderson for daring to sound light-hearted (with its allusions to Americana at its most kitsch) to contrast the rising tone of anxiety, at the realization the plane is going down.

<iframe width="1180" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson & SexMob, Prague 2023 - I, From The Air" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Many listeners remarked how prophetic both it and “O Superman” felt after the terrorist attacks of September 11th 2001, and it remained resonant in November 2024, when I revisited it on the cusp of a second term for Trump. The captain, after all, is a buffoon who uses the tannoy to announce the fact of his authority as much as any actual instructions of any use, only to abuse that authority by saying “…the captain says Put your hands on your hips / Put your hands on your knees / Ha ha…” By the end, it’s clear that the symbolic plane that is American technological supremacy is going down because the humans in charge aren’t as smart as those who actually built it, and with each decade we can find a new level to the allegory, wherein it’s American democracy that’s going down or (sorry to bash America, alone) any former superpower, or empire that might be committing economic suicide or, I dunno, playing party-games when it’s supposed to be steering us through a pandemic…

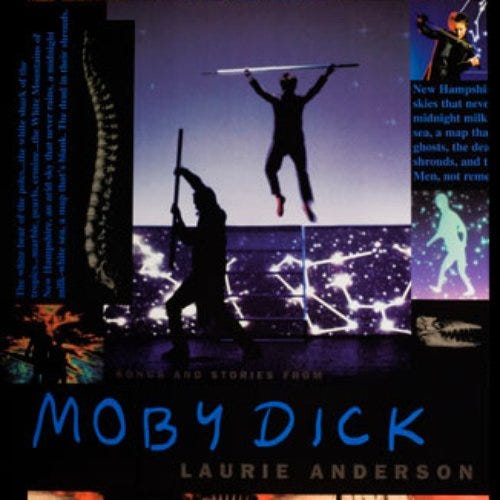

The social role of women was not yet a major preoccupation of Anderson’s work when she composed United States I-IV unless we consider the grand gesture of a woman working on an epic scale (with enormous projection screens on the stage and an eight-hour run-time across four days), which was much less common in the 70s & 80s, and seems more like the heroic, masculine gestures associated with the postmodern novelists of the 60s, 70s, and 80s (Gaddis, Pynchon, Barth, DeLillo) who sought to write the Great American Novel, or the various prog rock groups composing their rock operas or triple albums. There was a marked impulse toward epic following the ascent of America as a superpower, so as to establish cultural supremacy and/or to grapple with the contradictions of late-capitalism and life in the Melting Pot, but few did it with as much enduring humour as Anderson. (Fun fact: she once asked Pynchon if she could base an opera on his National Book Award winner Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) and got the response, “…only if it’s scored for solo banjo,” which she recounts as a very witty and polite way of saying No. At the turn of the millennium she took on Melville’s Moby Dick, the greatest of all American epics.)

In short, Anderson was very much an anomaly among female artists releasing albums on major labels in the 80s and 90s, but her approach was never simply “to prove that a woman could do what the men could” since the traditional, stereotypical association of femininity and domesticity (or having one foot in the nursery) came through in songs and stories that started out like whimsical ditties, or snippets of gossip, or idle conversation, before disclosing their far reaching significance. One can derive all kinds of morals but I prefer to think of her voice (literal and figural) as conveying the notion that one ignores women’s speech at ones peril, hence the use of the “Voice of Authority” (AKA Fenway Bergamot), a conspicuously synthetic, masculinized version of her own, making sinister pronouncements that we’re acculturated to hear as more authoritative at first, especially by contrast with a woman’s softer tones and higher pitch, but which often speaks absurdities.

Strange Angels (1989) was the second of Anderson’s albums I heard, and moves away from the mostly synthetic sounds at the start of the decade (accentuated in their artificiality by the occasional acoustic instrument), which conveyed a veneer of pristine, antiseptic modernity fitting with an idealized vision of consumer-capitalism. Thus, the whimsical melodies on one synth might be undercut by more sinister tones on another, or juxtaposed with the keen of the viola (her first instrument, preferred for its resemblance to the human voice at its most emotive). By now, Anderson’s music had evolved to encompass elements of what had been called “Fourth World Music” (i.e. Third plus First) by one-time collaborator Brian Eno, or just World Music, much of it introduced to Euro-Americans via the RealWorld label founded by another of Anderson’s collaborators, Peter Gabriel, who duets with Laurie on “Excellent Birds” on So (1986), originally from her own Mister Heartbreak (1984). The instrumental fills can sound showy – noodling and muso-ish in the insecure jargon of journalists raised on punk – but tend to be brief and discreet, fluttering in and out of the mix like exotic birds, or glimpses of those other cultures making their home in America’s Melting Pot.

(Aside: My closest friend in my mid-teens, the archetypal artist and hipster, had introduced me to Big Science as an amusing novelty but I’d also picked Strange Angels out of his father’s record collection for the very cis reason that her portrait on the cover captures her essence as one of the most beautiful androgynes in popular music history, giving me serious gender envy more than almost anyone I can remember during Puberty #1, only a few years after dysphoria kicked in. So, yes, despite a now-30-year admiration for this enormously cerebral and profound artist – this true Renaissance Woman for the late 20th and early 21st centuries – I might not be writing this if it weren’t for that envy… although that’s not to say we shouldn’t judge an album by its cover. Poised exactly between male and female, the Laurie on the cover seems to deliberately incarnate the perfect balance I personally sought, being aware from my reading of Jung (et alia) that the Androgyne had long been a symbol of spiritual fulfilment, or the harmonious integration of Ego and Anima / Animus. True, Patti Smith on the cover of Horses (1975) had popularized a kind of androgyny aligned with rock’s (and proto-punk’s) broad challenge to cultural norms, inspiring a generation of androgynous men and women in music, but Anderson elected to be lost in thought rather than surly, and her spiked crop seemed to allude to that easily neglected aspect of punk: that it provided a space for more female songwriters to express themselves without pandering to the male gaze or the taste of male record company executives.)

<iframe width="830" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson - Hiawatha (Hancher Auditorium, Iowa City 1990-03-12)" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

“Hiawatha” from Strange Angels may be one of the prettiest songs Anderson has ever recorded, using Longfellow’s epic poem as a startpoint for a collage of Americana that takes in Elvis and Eliot (‘“Goodnight, Ladies…”’ from “The Waste Land”) as if to signal her own stylistic and thematic intentions but also underscore how she leans more toward a vision of America as utopia than dystopia at the end of the Cold War. (Lou Reed fans might note that he’d quoted the same lines from Eliot on Transformer, which were in turn taken from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, as if Anderson’s tracing a kind of queer genealogy). From the same album, “Coolsville” is a strong contender for prettiest track, although the lyrics are predominantly ironic (‘…so perfect / so nice…’), and it’s the illusory prettiness of, say, LA at night viewed from a distance. There’s a comforting sense that that the cool, smooth, world of the near future epitomized by Silicon Valley, and the campuses of the major tech companies, might be a kind of attainable, immanent Heaven, defined by a lightness of being, but in the context of her greater body of work, it’s clear that such a utopia can only be built on the exploitation of poorer workers, elsewhere in the world-system.

<iframe width="996" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson - Coolsville" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Elsewhere on the album is her most conspicuously feminist statement, “Beautiful Red Dress,” which masquerades as an empty-headed pop number, punctuated with a spoken-word section that calculates the year in which the gender pay gap will be closed, delivering the punchline with a slow, quiet menace she’d use more frequently in the early 90s, without ever discarding her predominant soothing tone. It’s not a terribly nuanced satire but the withering sarcasm implicit in its parody of stereotypical womanhood is effective at illustrating the patronizing strategy of consumerism: to distract women from economic injustice by offering the trappings of femininity at its most decorous.

<iframe width="885" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson - Beautiful Red Dress (Official Music Video)" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

(I’d never seen this video until now and OMG is Laurie pretending to be Cyndi Lauper just as goals as the more familiar androgynous Laurie who looks a lot like Desire from Neil Gailman’s Sandman, around the same era, now I come to think of it…)

Anderson’s next truly great album, marking a third era in her musical evolution, was Homeland (2010), which retains elements of World Music alongside electronica of comparable compositional sophistication. Conceptually, Anderson’s use of synths was always ingenious but had a deliberate naïveté early on, as if performed by primitive robots just learning to speak and act in humanoid fashion. If anything, the electronic elements circa 2010 suggested AI on the cusp of the singularity: complex, intricate, close to surpassing human intellect. New, younger collaborators would guest on the album, including Anohni (then, Antony) providing wordless murmuring vocals on “Strange Perfumes” and Colin Stetson, just embarking on his New History Warfare trilogy, which made sense given his & Anderson’s shared debt to the classical minimalism of Philip Glass.

<iframe width="1180" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson performing Transitory Life" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Approaching the age of 60, Anderson contemplates mortality more and more often, and “Transitory Life” sees her mourning the lost girls in other timelines when “It’s a boy!” is uttered at birth, simultaneously announcing one destiny and foreclosing another. It’s one of her more “trans adjacent” moments, evoking a host of child spirits, hovering silently above the patriarchal world that she names one by one (until this particular trans parent is close to tears), and I’d like to imagine the song providing solace for trans listeners who want soothing rather than songs that vent rage (as seem to be easier to find). Transness, as I’ve said, has never been directly explored by Anderson, and yet androgyny is an ever-present characteristic of her style, and the interplay of more stereotypical masculine and feminine identities (whether in the characters in the lyrics or the actual voices juxtaposed), defining themselves through opposition, whereas the dominant voice shows synthesis is possible.

Trauma beneath the Ice

My favourite late work is probably the film Heart of a Dog (2015) which illustrates her ability to balance sentimentality, humour, and a disregard for hierarchy or conventional expectation entirely in keeping with her longstanding style, integrated with the Buddhist practice that increasingly informs her work. I won’t summarize it further, since its’s a continuation of many themes apparent from the outset of her career, but I’ll give a SPOILER of a moment from its emotional peak: when she recounts a moment from early childhood. Ever ambitious, she’d climbed to the top of the diving board at the local pool, completely missed the water, and landed on the side, breaking her back. She spent many weeks in hospital in a children’s ward mostly occupied by burns victims, whom she remembers in absurd contraptions like rotisseries for roasting chickens… …and would tell the story numerous times over the years, often focusing on the moment she was told she’d never walk again by a doctor, of whom she thought “This guy is crazy,” as if this were the seminal moment when she learned to distrust authority, or defy male expectations, and this was the moral of the story.

But it wasn’t.

One time she was re-telling it and, for some reason, she recovered for the first time in decades the memory of the ‘heavy smell of medicine’ and the actual sound of children crying through the night, and occasionally screaming, and the fact that in the morning some of the beds would be empty. As I heard the story unfold, not having seen the film since well before transition, I found myself tearing up rapidly, face contorted as if meat-hooks were pulling my mouth open at the corners, channelling every memory of every time my own children had been ill, or I’d been afraid, myself, thousands of miles from home as a child, and perhaps memories of all the children I’d seen in wards at Christmas, as a child, when we followed my father on his rounds. Strangely, though, I pulled myself out of what might have tipped into a prolonged CPTSD attack (or Anderson’s narration did) and I felt grateful for her sharing what must be one of her most painful memories (this from a woman whose father was incarcerated by his own father, a drunk, and who once rescued her infant siblings from under the ice of a lake after the pram rolled through it). She’s shown how we can use selective detail and mannered delivery to tease humour out of moments of horror… and how we can go deeper into the memory, too, when we’re ready to, even if it’s taken years. This is how we live, or make life liveable, but at some point we need to actually open the door to the basement of our brain, and hear the sounds and smell the heavy smell of medicine, rather than telling ourselves we’re well adjusted because we can see what’s down there.

<iframe width="1180" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson - Heart of a Dog [Official Trailer]" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

I’m drawing to a close, now, because that’s more or less the point I was building towards, before a more gentle conclusion. Even in the course of my deep dive into her work, it takes a while to remember that scattered across it are visions of an absolutely apocalyptic future and personal memories of horrific trauma, surpassing the average person, but she’s cultivated such an awareness of the sublime & the beautiful that’s immanent, that the overall effect is to reconcile the listener to both, and what seems like the random plotting or track sequencing is more like mindful contemplation – not running from the dark or into it but drifting through it until free association takes her somewhere happier to explore but not cling to. And that’s what I mean by “What Would Laurie Do?” in times likes these.

<iframe width="1180" height="664" src="

title="Non-Metaphorical Decolonization by Mount Eerie (official video)" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

By coincidence, alongside Anderson, I’ve been diving into the back catalogue of a much younger man (albeit a year older than me) who may be one of the best artists of his generation at producing memoir in musical form. I wasn’t fully conscious that’s what I was doing, at first, just that Laurie Anderson and Phil Elverum (AKA Mount Eerie) both have incredibly soothing voices as they narrate anecdote from the America wilderness with a very neo-Romantic & Buddhist sensibility; in Elverum’s case, the Buddhism filtered through West Coast poets like Joanne Kyger (who gives the new album, Night Palace, its title, and Gary Snyder, the great eco-poet of the 60s and 70s, whose contributions to eco-politics and ethnopoetics also underpin Elverum’s work as a songwriter, partly employed in forest management). A few days after this, I realize Anderson is slightly older than my mother, and Elverum a year older than me (with a fair resemblance to the person I might have been if I hadn’t transitioned); perhaps their appeal is to show me where I might plausibly be going, with so few elderly trans role models, and how I might have managed to reconcile myself to the world if I’d been a cis guy (or kept pretending to be one).

Anderson’s latest work is Ark: United States V (2024), which debuts in Manchester later this month, imagining a global ark, literally and figuratively in our moment of geopolitical crisis and fear of environmental collapse. She also recently released an album about Amelia Earhart (2024), bringing together some of her oldest themes and motifs, but also placing a heroic female centre-stage who found fame in a previously male domain and seems like an obvious role model for Anderson herself. In an interview preceding the album, she says with a laugh that when she thinks about contemporary crises she could easily shoot herself if she weren’t such an optimist, and while I wonder whether I’d be able to maintain such optimism myself without her belief in an afterlife, I’m not sure how much that matters when one has cultivated her kind of ability to move backward and forward through time in her imagination. Songs from the Bardo (2017) bears out her commitment to years of Buddhist practice and, if I could only pick one track, “Lotus Born” may be one of the most simultaneously beautiful and sad songs by anyone I can think of, cutting to the very core of what it means to be mortal; Anderson gives one of her greatest vocal performances, balancing urgency and compassion when she sings the line about the moment of death being like the pain of a landed fish, while conveying the sense that she is nonetheless there with you, comforting you by assuring you there is a narrative here, there is a destination, even if no-one has been able to report back, and all suffering is transitory.

<iframe width="1180" height="664" src="

title="Laurie Anderson, Tenzin Choegyal, Jesse Paris Smith - "Lotus Born, No Need to Fear" [Official Audio]" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

![Big Science [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl Big Science [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F632dd2d7-47dc-4fb9-b17d-0810248899c1_1000x1000.jpeg)

![Strange Angels [VINYL] by LAURIE ANDERSON: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl Strange Angels [VINYL] by LAURIE ANDERSON: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6939c6b8-f427-4185-812a-ad1a64642f20_894x949.jpeg)