Teaching "An Inspector Calls" (1945) as a Trans Woman in 2024

A series within the series on how transition has changed my relationship to certain texts, and the responsibilities they enjoin upon me as a teacher

Since starting HRT, I’ve been acutely aware of how hormones have mediated my relationship to my children – the connexion has become ever stronger despite being as strong as I could imagine, already – as well as how that relationship is mediated by the books and cartoons and films they love, some of which I once loved, the enjoyment of which is intensified by watching their response to them, eyes glistening in the screen-light or bedside-lamp-light.

I can’t say my relationship to my students has changed in any way I’ve noticed, other than that the fear of how much the closeted trans kids across the UK must be suffering through these times sometimes hits me with acute, physical symptoms of anxiety. For the most part it’s my students’ lack of response to my transition that’s been so gratifying: I’ve learned that Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2012) are fundamentally different from my own, Gen X, in that the vast majority are unfazed at the prospect of a trans teacher and respectful in their occasional questioning; they correct themselves and apologize when they get my title wrong, they correct each other, and in doing so they make me feel accepted.

But what has changed is how the act of teaching young male (or, at least, AMAB) students has mediated my relationship to the texts I teach, and not the other way around. That’s to say, the fact of explaining certain texts and exploring them as someone feminine-presenting, and with a feminized body, has changed my perception of those texts or, more accurately, my sense of responsibility to use these representations of women as carefully as I can so as to shape these young men’s understanding of feminine presentation, female embodiment, and gender-relations considered as power-relations.

Unimaginative though it may sound, An Inspector Calls (1945) was my go-to text for years with girls (aged 13-14), as a springboard to introduce some watered down Marxist and Feminist literary theory, which is exactly how I teach it to boys (aged 14-15) at my current school since what’s good for the goose is good for the gander, whether or not you believe in the “maturity gap” between them. It’s gratifying to not have discovered some deeper level of analysis for having transitioned (because, duh, we’re cognitively the same), and even if my essay questions over the years have often focused on the relative guilt of each member of the upper-middle class Birling family for their respective roles in the downfall and suicide of working-class Eva Smith, rather than how she would have felt in the months leading up to her suicide by drinking bleach (it occurs to me now), the play as a whole is a nuanced analysis of how privilege clashes with morality, and how vital were the introduction of employment laws, the minimum wage, birth control, two world wars, and so on, for women’s advancement between 1912 and the present.

The events of the play are set (supposedly…) after her death (…which I’m not explaining if you haven’t seen or read it) so we’re not compelled to imagine her despair and actual suicide at length (which might have been unbearable, preventing it from being staged and studied so often, almost 80 years after it was written, and students have never dwelled on it, either. Did I find myself tearing up at the ending of the film as much before HRT as I did when I last screened it (i.e. the first time since “going full time”)? I doubt it, but I wasn’t heartless, either, and I was already a parent before I first taught it, so I’d lost a few layers of skin in the process. What makes me suddenly see myself from the outside, as I’m teaching the play to a class in 2024, is the exchange near the beginning, just after the 20-something son has returned to the dining room where his factory-owner father, Arthur Birling, and his slightly-older, soon-to-be brother-in-law, Gerald Croft, are discussing manly matters, hence Eric tries to impress the pair with some casual sexism or, as the youth would say, bantz:

Eric: Mother says we mustn’t stay too long. But I don’t think it matters. I left’em talking about clothes again. You’d think a girl had never any clothes before she gets married. Women are potty about ’em.

Birling: Yes, but you’ve got to remember, my boy, that clothes mean something quite different to a woman. Not just something to wear – and not only something to make ’em look prettier – but – well, a sort of sign or token of their self-respect.

It’s at this point I wonder how I’m perceived as a 6’3” AMAB person in a dress or skirt, with a touch of concealer as well as mascara, in any given day. To address Birling’s first premise: am I trying to make myself look pretty? Sure, to some extent, but how do we distinguish physical attractiveness from aesthetic appeal? “Pretty” tends to connote delicacy, fragility, and vulnerability, in addition to the basic denotation of beauty, and these in turn can suggest passivity and submissiveness before the male gaze, which is of little concern to me as a queer trans woman. I’m not ashamed to say I like looking pretty but when I’m most pleased with my appearance the word I use inwardly is “cool” (whether or not anyone else would agree!), rarely “hot”, and never “fashionable,” probably because those other connotations of prettiness aren’t ones that appeal. “Cool” for me denotes an expression of personality that is distinct when it’s spotted but isn’t desperate to be seen; it can suggest aloof and independent but shouldn’t be cold or self-regarding. The concept wouldn’t have been entirely alien in 1912 and the term was used in ways that overlap with more popular usage after the mid-century but it tended to be almost pejorative, being a few degrees from the misogynist “frigid” since it hadn’t yet become attractive to project independence.

Self-evidently, women have a broader palette of colours and, metaphorically, patterns, textures, and silhouettes, to work with. Some of these are pretty but a holistic impression of cool can often arise from blending the pretty and the functional or even historically masculine. How much these combinations can convey a complex or nuanced personality (or just mood, in any given day) is debatable: like the form of a poem, according to Charles Olson’s famous maxim, clothes are ‘…only ever an extension of content.’ They enhance, accentuate, and inflect aspects of ones appearance as well as ones behaviour and demeanour but that’s about it. Cis-normative men, I’ve always thought, are put under greater pressure to express their personalities more through their actions and speech, since they dress within narrower parameters, if not in actual uniforms. For at least 35 years, I felt that restriction as a cruel imposition in any given day: gender envy almost palpably ached, although I wondered how much that was something dysphoria seized upon, as if the basic discomfort of having the wrong hormones was a fluid that circulated in my body the way Freud imagined the psychical drives having a kind of hydraulic action: press down in one place, and the discomfort will emerge elsewhere, depending on the particular fissures and weak-spots in the psyche.

When I started to investigate the neuroscience-of-being-trans further, I encountered the idea of dysphoria as potentially a kind of psychical feedback, or cognitive dissonance, as the trans brain that developed down the feminine pathway (in my case) constantly feels unnerved by encountering a body with a different map to that expected (a sort of phantom extremity pain for extremities that never were…). I’m not sure where I encountered - or if I just invented - the theory that the brain looks outward, too, for the 51% of the species whose brains run optimally on the same hormones as ours, and seeks their approval through emulation and integration… only for those drives to clash with our socialization among the testosteronal-tribe, for whom the primary signals of group allegiance are definitively Other, in a strict binary enforced by the threat, or exercise, of violence. Thus: the dissonance, the incongruence if not dysphoria, the brain fog (for many), and the intrusive thoughts that hold us back from feelings of normality and calm (to say the least) when they’re not actually killing us, bit by bit.

18 months after starting HRT, full-time feminine presentation gave a distinct boost to the euphoria, contentment, and general feeling of being at ease with myself that estradiol alone had already given me (while I was still mostly presenting masculine), overwhelming any increase in anxiety (about rejection, ridicule, if not actual violence) that might also have been expected to kick in. Any euphoria that might be imagined to stem from the expectation of attracting anyone is negligible in my case: I’m married, monogamous, far from libidinous, and would have noticed by now if there were any disappointment that I’m not turning heads. The occasional compliments from women are gratifying but I’m not chasing these either; in short, it really does seem that feminine presentation (as a supplement to female embodiment) is an end in itself, regardless of what one might imagine both or either might do for ones status, attractiveness, etc. I can honestly say that transition serves to satisfy an inner compulsion, far more than feminine presentation serves to manipulate interpersonal dynamics, as is often imagined by men (and, far too often, women) who can’t imagine a woman thinking or behaving except in relation to men.

So, No, Mr Birling, clothes are a sign of group allegiance, an expression of personality, and only a token of self-respect if we understand (as he almost certainly didn’t, in 1912) that gender expression or presentation is but one token among many, a list of which he neglects to enumerate although I suppose we could work our way up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, considering how much a woman has achieved in her career, and/or achieved on behalf of her family, and/or achieved by finding a partner (whatever their respective incomes), with self-actualization at the apex, whether that’s artistic achievement or spiritual fulfilment or what have you. For Mr Birling, upper-middle class men would be expected to provide most of the standard Needs (shelter, food, etc.), so long as they provide them with children and function as a liaison to the servants… or just let themselves be used as a token of their own self-respect. I don’t think I ever articulated this to students at such great length before because the phrase ‘…a sign…’ as opposed to ‘…the sign…’ implied he isn’t entirely wrong, even if none of the characters spell out what else might be a token of women’s self-respect.

Ideally, expression of personality through appearance should be separable from sexuality and yet it may be impossible to fully disentangle gendered presentation from the means to appear more physically attractive (whether that is, in turn, denoted “pretty” or “handsome” or what have you) because clothes, hairstyles, and make-up have almost always been designed to accentuate secondary sexual characteristics (and, in some cases, primary, although most workplaces have dress codes that indirectly serve to conceal these). No matter how much I maintain that enhancing any attractive features (or increasing general attractiveness) is a distant second to the expression of taste and personality for me, I’m imitating gendered codes and “gendering,” historically has been a way of signalling a social class with specific expectations vis-a-vis labour and the reproduction of labour.

Personally, I think my combination of presentation and physique is only ever going to confine me to a third class whom the majority of people I meet are inclined to tolerate… until they don’t. I can’t actually speak for cis women, just offer some observations from my slightly closer vantage point here in No Man’s Land. The net effect is: I don’t make anyone stare or gawp in a good or bad way, which is definitely a win for a lot of 40-something TransLaters, for whom changes will be slower and slighter. My dysphoria became much more easily manageable very quickly after starting HRT (big win), and almost negligible after I went full time (massive win). A lot of cis women my age probably feel a lot worse than I do about their own appearance, with or without the amortisation that childbirth and childcare can bring. I like my slender, hairless forearms; I’m okay with the fact that my hands are large… although I like that the veins have flattened and the fingers would be slender for a man. My legs are long and shapely… albeit that my hips are those of a boy; my chest-waist ratio is probably quite attractive… for a guy; my cup-size is probably smaller than a lot of cis-men my age but they lessen the dysphoria simply by being there, and that’s all I need them to do. Overall: any gain in youthfulness (from smoother skin, rounder cheeks, a lick of make-up) might be offset by the potential absurdity of being an AMAB-person-in-a-dress but, 90% of the time, I don’t care. Also a massive win. Allowing these physical changes to be legible, partly through the clothes I wear fearlessly, publicly, these days, makes them a token of my self-respect, for sure, but there’s a lot of backstory here, and that’s not going to be apparent to most men and many women, although the latter will understand how much more is at stake than being pretty for the sake of the male gaze.

I’ve probably read far too much into two lines of the play, so I’m going to turn now to the section, towards the end of Act One, in which it’s female-on-female gender envy that shoves Eva Smith a further rung down the social ladder, having already been fired from her first job for organising a strike to protest for fair pay. When Sheila Birling gets Eva fired from her next job, she isn’t blamed by Priestley for being a petty and vapid, archetypal woman – in fact, she’s the quickest to show sincere remorse, and to learn from the experience, by several metrics (the fewest pages to confess… the strongest emotions… the most dramatic character arc). What’s indirectly revealed through her role in Eva’s downfall is how the specific misogyny of the upper classes (treating women as a token of men’s self-respect, and little else) causes them to internalize that misogyny and then turn it outward, mistreating fellow women who have more of that precious commodity – “prettiness privilege” – which can sometimes trump class privilege when it comes to attracting the financial support of men… albeit temporarily and precariously.

Even before Sheila learns, in Act Two, how her fiancé came to support Eva (by then known as Daisy Renton) she intuits this imbalance of power between women that can cut across class barriers, since women’s class privilege (no matter how great it might be in each individual case) is to some extent contingent on the consent of men:

Sheila: (distressed) I went to the manager at Milwards and I told him that if they didn’t get rid of that girl, I’d never go near the place again and I’d persuade mother to close our account with them.

Inspector: And why did you do that?

Sheila: Because I was in a furious temper.

Inspector: And what had this girl done to make you lose your temper?

Sheila: When I was looking at myself in the mirror I caught sight of her smiling at the assistant, and I was furious with her. I’d been in a bad temper anyhow.

Inspector: And was it the girl’s fault?

Sheila: No, not really. It was my own fault. […] I’d gone in to try something on. It was an idea of my own – mother had been against it, and so had the assistant – but I insisted. As soon as I tried it on, I knew they’d been right. It just didn’t suit me at all. I looked silly in the thing. Well, this girl had brought the dress up from the workroom, and when the assistant – Miss Francis – had asked her something about it, this girl, to show us what she meant, had held the dress up, as if she was wearing it. And it just suited her. She was the right type for it, just as I was the wrong type. She was very pretty too – with big dark eyes – and that didn’t make it any better. Well, when I tried the thing on and looked at myself and knew that it was all wrong, I caught sight of this girl smiling at Miss Francis – as if to say: “doesn’t she look awful” – and I was absolutely furious. I was very rude to both of them, and then I went to the manager and told him that this girl had been very impertinent – and – and – (she almost breaks down, but just controls herself.) How could I know what would happen afterwards? If she’d been some miserable plain little creature, I don’t suppose I’d have done it. But she was very pretty and looked as if she could take care of herself. I couldn’t be sorry for her.

Inspector: In fact, in a kind of way, you might be said to have been jealous of her.

Sheila: Yes, I suppose so.

Inspector: And so you used the power you had, as a daughter of a good customer and also of a man well known in the town, to punish the girl just because she made you feel like that?

Sheila: Yes, but it didn’t seem to be anything very terrible at the time. Don't you understand? And if I could help her now, I would---

Inspector: (harshly) Yes, but you can’t. It’s too late. She’s dead.

Pretty is the word most often used of Eva Smith by almost every single character (with the notable exception of Mrs Birling), in spite of the resourcefulness, moral integrity, and independence she demonstrates right until her suicide and, perhaps, through that very act. Her prettiness is implied to have been a factor swaying Mr Birling to bait her with a promotion to call off the strike; it led Sheila’s fiance, Gerald Croft, to protect and support her even without the immediate expectation of sex; it probably led Eric Birling to steal money for her, rather than just discard her. Nonetheless, her many virtues led her to refuse to exploit the best asset she had in the eyes of the class for whom prettiness is almost all there is to a woman. To be a source of labour or a site for the reproduction of labour: these are the main roles of women under Capitalism, and the only way one might hope to reduce the former is to increase the latter, with all its attendant risks, trading privilege for privilege.

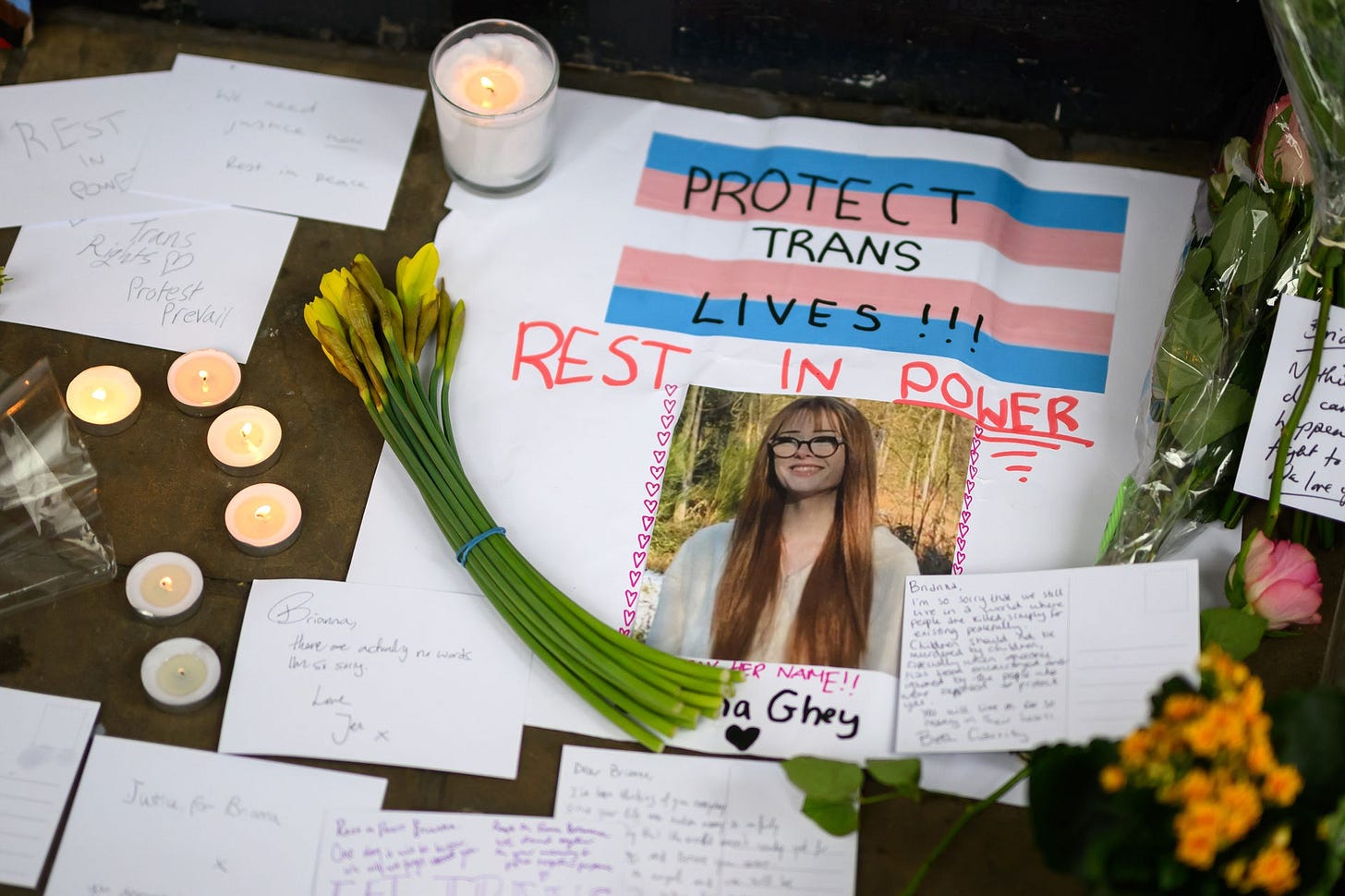

Note how honest Sheila is about the pettiness of what she did – and might not have done ‘…if she’d been some miserable plain little creature…’ which simultaneously reveals the privilege that comes with looks… and the precariousness. If that’s someone’s main privilege, the lack of other privileges can make it so much more tempting to destroy that person. Some of the horrific details we learned during the trial of Brianna Ghey’s murderers, a teenage girl and boy, were that the former extensively planned the torture of a girl she referred to as ‘it’, speculating whether Ghey would sound like a boy or a girl as they killed her. One motive was intense envy of Ghey’s appearance, which she wrote about at length, although it must also have been easier to dehumanize someone who belonged to a group dehumanized if not demonized every day in the Press, by numerous journalists and actual MPs in the year leading up to the murder – precisely the kind of respectable authority figures Priestley points out are wont to exploit and abuse women.

The selective use of pronouns and common nouns but not actual names is something I point out to my students every year but this was the first time I linked the behaviour of Brianna’s killers to the pattern in the play of referring to Eva Smith as ‘a girl,’ ‘the girl,’ one of many ‘girls of that sort,’ and so on, the characters always distancing themselves from the flesh and blood person, with her rounded character, complex backstory, and far more courage than every single one of them. (Maybe I’ll do this next year, on the second anniversary of Brianna death, if I have a Year 10 class, again.) When Mr Birling talks in abstractions, even before the Inspector arrives, describing his ‘duty’ to ‘Capital’ as if it’s a moral obligation to a higher power, rather than a feeble excuse to exploit workers, he already epitomizes the harm done by distancing oneself from ‘the girl’, whom the Inspector conspicuously refers to by her name or as ‘a young woman’, restoring her respect and humanity, as is his purpose in the play. Only occasionally does the Inspector call her a ‘girl’ when he needs to emphasize her vulnerability, although he also shifts to grotesque dysphemisms, describing her lying with ‘burnt-out insides, on a slab’ so as to shame the Birlings, provoking horror and grief, but ultimately, to teach them.

It hasn’t occurred to me until now, as I’m writing this piece, that every time I read about some trans person who came out in their teens, only to be assaulted or killed, I think of them as infinitely braver than every single MP or Senator or newspaper columnist could ever be (and 25 years braver than me) so, in this respect, each of them is an Eva Smith or, as the Inspector says in his final speech, ‘a John Smith’ of whom there are ‘millions and millions and millions’ and ‘we are all one body’ – one of the rare Christian allusions hinting at Priestley’s purpose but sounding so much more resonant and rich in unintended associations for this particular trans woman in 2024, the day she taught that scene for the 6th or 7th time.

We are all one body. (Author weeps silently as curtain falls)

POST-SCRIPT:

I wrote the first draft of this on the evening of March 6th and then procrastinated for over two weeks for reasons too complex to go into, although possibly worthwhile at some point in the future. The following day, Nex Benedict (above) was beaten up by three girls in a high-school restroom in Oklahoma, and died of an overdose the following day, although the world didn’t know this for another two weeks, and many assumed a concussion. The body of a murdered trans woman was discovered in Mexico the same day, and a trans man was abducted and murdered in Utah ten days after that. The past fortnight I’ve found it hard to teach the trial scene from To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) without choking up because this, too, shouldn’t feel so relevant, in 2024. Optimistically, I tell myself it’s a privilege to get to teach these texts and that I have a duty to show these young men in my charge it’s okay to be visibly pained by the act of reading, while also being in awe at the talent of writers long dead to bring these people to life who might otherwise be abstractions. I don’t know whether the human species will still be here in 2088 to study the novel or play or screenplay or future-medium-yet-to-be-devised that draws on the lives (and deaths) of Brianna, Nex, and innumerable others (just as “Tom Robinson” condensed the Scottsboro Boys into one) to teach people compassion but I do know that, in a sense, that hypothetical text isn’t needed once we understand how narratives serve to elicit empathy for marginalized if not oppressed figures who are all, potentially analogous, teaching us to see ourselves in others. We are all Tom… and Eva… and Brianna… and Nex, whether cis or trans, Black or White, one of the First Peoples (as Nex was) or colonists.

We are all one body.