TRANS DISCOURSE & THEORY: A PRIMER

A short reading list for trans people and allies looking to understand the state of contemporary discourse about a range of trans issues without heavily academic language.

The following primer is not intended for academics but for trans people and allies looking to understand the state of contemporary discourse about a range of issues in the 2020s from the perspective of trans and non-binary authors, writing for an adult audience. [[1]] To my mind, there are several claims that should be axiomatic, or ‘inalienable truths,’ and are often treated as such by trans writers while being disputed, ignored, or greatly distorted by many cis writers. These are some of the texts that allow us to substantiate the following:

· Trans people exist everywhere, in every culture, and have always existed.

· Gender identity does not neatly align with sex, as determined by observation of genitals, nor do genitals always correspond to chromosomes. Gender occurs on a spectrum or continuum.

· Sex and gender are not universally binary in the animal kingdom, nor is heterosexuality the rule in other species, with homosexuality associated with no disadvantage to individuals. Trans people are much more likely to be queer (i.e. L, G, B, Pan-, Ace- etc.) hence we should be assumed to be allies if not “under the umbrella” already rather than separate.

· Transition need not be a surgical or medical phenomenon for a person’s transness to be authentic; at present, a small majority of trans people seek hormonal transition, and a large minority seek surgical transition.

· Being trans is not a psychiatric disorder, nor is it caused by trauma, although it does predispose us to being abused, discriminated against, and ostracised, which can compound mental illness.

· Trans people are more likely than cis to be raped, assaulted, and murdered; trans women are much less of a threat to cis women than cis men, and (arguably) non-gender-conforming cis women are more likely to be the victims of harassment or assault by other cis women as a result of transphobic discourse.

· The existence of trans people challenges the dominant idea of a sex/gender binary, and hence presents a threat to late-capitalism and patriarchy.

· Trans healthcare is not “too easy” to access, and waiting lists are longer than for most procedures affecting cis people, contributing to the high incidence of suicide.

· Trans activism is not opposed to feminism and is often consciously intersectional to a greater degree than other movements because trans people recognize that we appear in every society and class regardless of dominant beliefs.

· Trans people are significantly more likely to be neurodivergent and somewhat more likely to be disabled but neither of these things should be used to invalidate us, not least because we are slightly more likely to achieve degrees and have higher IQs, rather than being cognitively impaired.

Taken together, these ten axioms could easily be framed as a “contested ideology” (as the UK’s Department for Education, under considerable political pressure, has done, less than a year before the Trump administration set out to erase “gender ideology” from every institution). Most trans people would agree with most of these (although we can be sceptical due to internalized transphobic discourse), and yet many of these axioms might surprise cis people and require extensive explanation and evidence, seeming radical or cutting edge.

In terms of authorship, the texts listed below are admittedly Eurocentric and trans fem heavy which I will attempt to remedy in future writing (and already am in my reading) but the writers themselves are aware of this and often address intersectionality as well as breaking down statistics so that we can see the relative incidence of violence, healthcare provision, income, mental health problems, etc. across classes, genders, ethnic groups, etc.. It’s notable that most of these writers present their arguments with far more academic rigour than most broadsheet journalists, although the publishers are mostly not university presses.

If anyone objects that there are no cis authors here, they are missing the point: the state of public discourse in the 2020s is dire, with journalists and columnists across the political spectrum from the Telegraph to the Guardian regularly quoting gender-critical groups without contacting a single trans person, and presenting hypothetical risks (that rest on offensive prejudices) without stating the actual incidence of crimes or the actual accessibility of healthcare. This, then, is where I’d recommend starting:

Transgender Marxism (2021), ed. Elle O’Rourke & Jules-Joanne Gleeson

The term “transsexual” (coined in 1923) has tacitly framed our identity within medical discourse for over a century, and while “transgender” was coined in 1965 so as to shift the emphasis from sexual activity to actualizing inner gender identity as a motive for transition, it didn’t completely eradicate this bias since it was used in the 80s to label a broad demographic disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, because our forebears were so often forced into sex work.

At the turn of the present decade, Transgender Marxism arrived as a powerful corrective, reframing trans identity within discourse about class, and as individuals whose transition narratives are greatly influenced by class. One of the most memorable theses is that trans people are a threat to late-capitalism because our very existence destabilizes the cis-het family as the principal site of reproduction of the workforce and hence calls into question all values reproduced (symbolically) with each generation. (This writer is, full disclosure, the proud trans mum of the two best little allies in the world.)

It should go without saying that trans people exist everywhere, in every culture and class, and always have done, although what transition and gender expression look like has varied enormously across human history. It is a right-wing fantasy – or outright lie – that we are a modern invention, and our incidence has increased; trans people who seek, or would benefit from, medical intervention comprise roughly 0.5% of the population in any given country. Instead, public awareness increased greatly in the 21st century, just as some societies became wealthy and tolerant enough for more people to medically transition, and to do so younger (in the 2010s), the Right pushed back, violently.

While it is true that access to trans healthcare varies wildly by socio-economic background, it is also striking to note that many ostensibly privileged people will find themselves temporarily or permanently in the precariat if not the lumpen-proletariat during transition, which is nonetheless done in defiance of capitalist logic, so integral is gender to identity. (On a personal note, this writer briefly reached the top 10% of earners, presenting as a cis-het man, and then fell to the median within a year of “going full-time,” presenting as a trans woman in every context, before returning to the 75th percentile 18 months after transition; other high earners of my acquaintance have lost considerably more, and the more affluent trans people tend to be those who are able to work remotely, whether or not they are out to colleagues.)

Even once trans people are comparatively assimilated (and have enough disposable income to resume being consumers) transness itself problematizes the ways in which the sex and gender binary keeps humans (in all their variety, along a continuum) in a state of constant dissatisfaction that we’re acculturated to palliate through consumption rather than, say, the pursuit of (self) knowledge and other forms of self-actualization.

As well as addressing “Transgender Identity Development in Community Context” (ch. 1), the contributors explore “Employment Trajectories” (ch. 2), position Judith Butler among the “Foundations of a Transsexual Marxism” (ch. 3), explore “How…Gender Transitions Happen” (ch. 4), “The Bridge between Gender and Organising” (ch. 8), and the relationship between “Transgender and Disabled Bodies” (ch. 10).

Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (2007), by Julia Serano

The importance of Dr Julia Serano to trans discourse cannot be overstated. Although her academic background is in molecular biology, Serano’s major contribution may be the refinement of discourse about trans identities in society by coining a large number of terms that enable us to probe how we have been conceptualized.

Serano’s main works are Whipping Girl (2007), Excluded (2013), Outspoken (2016), and Sexed Up (2022). Whipping Girl is effectively a manifesto arguing that transphobia is rooted in sexism and transgender activism is intrinsically feminist. One of the main topics is transmisogyny but she also explores trans-objectification, trans-facsimilation, trans-sexualization, trans-interrogation, trans-erasure, and trans-exclusion. Serano argues that sexism in Western culture may be subdivided into traditional sexism (‘the belief that maleness and masculinity are superior to femaleness and femininity’) and oppositional sexism, (‘the belief that female and male are rigid, mutually exclusive categories’). Serano coined the term effemimania to describe the obsession with male and trans expressions of femininity, which is rooted in transmisogyny, and cissexual assumptions to describe the belief among cisgender people that everyone experiences gender identity in the same way. Since cisgender people lack discomfort with their AGAB, and tend not to think of themselves as – or wish they could become – a different gender, they project that experience onto others, assuming that everyone they meet is cis. This, she says, is invisible to most but ‘those of us who are transsexual are excruciatingly aware of it.’

Serano’s more recent articles include refutations of the pseudo-scientific concept of autogynephilia, still causing shame and distress for trans women 20 years after being debunked, and her most recent full-length book focuses on the sexualization of (trans) women, drawing more on her experience of transition than in previous works.

The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice (2021) by Shon Faye

From Faye’s own prologue: ‘Trans people have endured over a century of injustice. We have been discriminated against, pathologized and victimized. Our full emancipation will only be achieved if we can imagine a society that is completely transformed from the one in which we live. This book is primarily concerned with explaining how society, as it is currently arranged, often makes trans people’s lives unnecessarily difficult. Yet, in posing solutions to these problems, it does not limit itself to thinking solely about trans people, but also encompasses anyone who is routinely disempowered and dispossessed. Full autonomy over our bodies, free and universal healthcare, affordable housing for all, power in the hands of those who work rather than those privileged few who extract profit from our vastly inequitable system, sexual freedom (including freedom from sexual violence) and the end to the mass incarceration of human beings are all crucial ingredients in the construction of a society in which trans people are no longer abused, mistreated or subjected to violence. Such systemic changes would also particularly benefit everyone else forced to the margins of society, both in the UK and across the world.’

Faye (b. 1988) trained as a lawyer, before pursuing writing and campaigning, working in the charity sector with Amnesty International and Stonewall. She was an editor-at-large at Dazed, and has been published by the Guardian, the Independent and Vice, among others. She also launched a podcast series, “Call Me Mother,” interviewing trailblazing LGBTQ elders. As her prologue indicates, Faye is greatly concerned with intersectionality, which is often presented as a strategic necessity by trans theorists (given our numbers) as well as an inevitability (given our universal provenance).

Transgender History (2008, revised 2017) by Susan Stryker

Although US-focused, Professor Stryker’s history (from the 19th century onwards) is vital for understanding how transness has been conceptualized, constructed, and constrained in a nation with disproportionate influence on the world-stage as we have moved toward greater self-determination in the 21st century only to be under threat of having many rights taken away once more in developed nations. The book’s five chapters focus on different historic periods, starting with an overview of terminology, and offering one of the more useful definitions of what it means to be transgender that privileges no particular model of transition: ‘…people who move away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross over (trans-) the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain their gender.’ This is, effectively, a definition that decentres Western notions, implies the value of an anthropological perspective, and potentially demedicalizes or depathologizes a category so often elided with the medically constructed “transsexual.”

The second chapter considers how our identity was pathologized (or inscribed within surgical and psychiatric discourse) from the 1850s to the 1950s, while tracing the origins of transgender activist movements. For much of this time, homosexuality and transsexuality were conflated and muddled. The pioneering work of Magnus Hirschfeld in Weimar Germany is discussed which helped bring about greater transgender visibility, although it was still collapsed together with crossdressing by many, and it has subsequently been argued that the most prominent activists were comparatively privileged cis male CDs who wanted to destigmatize their behaviour without fighting for the right for healthcare and the specific needs of other groups.

The third chapter documents a period of more violent struggle contemporaneous with the civil rights movement from the 50s to the 70s, including the Stonewall Riots that were led by trans activists. The fourth chapter then moves to what Stryker calls “The Difficult Decades” when Transgender Liberation faced a backlash from feminists and LGB activists, in the 70s and 80s, as their advances were felt to be compromised by association with a group that had been historically pathologized, and continued to be, after cis gay people ceased to be considered intrinsically subject to disorders (from 1973 in the UK, although it took until 2013 for Gender Identity Disorder to be reclassified as Dysphoria). Problematically, activism was dominated by trans women, and the threat posed by AIDS made organisation around a range of issues more difficult as priorities shifted to survival and mutual support.

The final chapter examines a period from the 1990s to the start of the first Trump administration (in the revised edition) characterized by improvements in healthcare and greater consideration of the differing subjective experience of trans people, as there was more recognition that the medical gatekeepers of the past had inadvertently compelled diverse individuals to conform to a narrow version of femininity. Stryker therefore ends her narrative shortly after the “Transgender Tipping Point” at a time of comparative optimism, before yet another backlash.

Trans: A Memoir (2015) by Juliet Jacques

Jacques’s memoir is based on her column for The Guardian (2010 – 12) documenting her transition at a time of comparative tolerance, after Section 28 (1988 – 2003) and AIDS but before the “Tipping Point” (2013), interspersed with a sketch history of trans people across the centuries. Its intercutting of relatively conventional memoir with more cerebral analysis of how trans identity has been presented in medical and psychiatric discourse reflects her frustration with the metanarrative of such memoirs (by the likes of Christine Jorgensen, Jan Morris, and April Ashley) while compromising just enough to get published at all by giving the reading public a measure of what it wants: a memoir that starts with a sense of insecurity and incompleteness and ends at the point where the trans person has more or less passed or become stealth, indirectly affirming the normality of the gender binary.

Jacques was therefore integral to beginning the process of bringing our emergent culture into the public eye, rather than just representing the life of an unthreatening individual. Her column was roughly contemporaneous with “Balls Out” by Casey Plett, which was serialized at the McSweeney’s Internet Tendency website, and launched her own career as a fiction writer. Jacques has since published the essential Front Lines: Trans Journalism 2007-21, which might sound niche but covers LGBT experience in war-zones, across different cultures, and trans (self) representation in different cultural forms.

Who’s Afraid of Gender? (2024) by Judith Butler

In academia, the importance of Butler’s seminal work Gender Trouble: Feminism and Subversion of Identity (1990) is undoubted and I have no wish to contest that here, although it also has a reputation for being abstruse and almost impenetrable that is not entirely unfounded. Butler’s 2024 work more or less picks up where Stryker leaves off, providing an accessible overview of how we reached our current moment (the post-pandemic rise of Fascism in the West) wherein trans people have become a “phantasm” cathecting the many legitimate fears of cis people onto an imaginary version of trans people somehow responsible for the worst crimes that, statistically, cis men are more likely to commit, even after we take our small proportions into account.

The pretext for much of this has been to cast rightwing governments as “defenders of women and children” despite ample evidence they have done far greater harm. There’s no denying that many aspects of life have been made harder for cis women, even those on a higher income or in higher income households. Even the most affluent women in the UK may have to cope with their children having the worst mental health in Western Europe, which is often worse than the national average for high-achieving girls (like my former students). The average parent in the UK spends 29% of her income on childcare; Sure-Start centres were mostly closed under the Tories, as were refuges for most victims of domestic violence; trust in the police is at an all-time low after the murder of Sarah Everard and police brutality at the vigils; rape convictions continue to decline from their single-digit percentage.

Butler recounts how similar trends in the US and other countries have led to the widespread strategy of scapegoating trans people, when the true existential threats to us and our children are environmental degradation and the collapse of ecosystems capable of sustaining human life in our children’s lifetimes; behind these threats lie neoliberalism, extractivism, neo-colonialism, and the historic legacy of colonialism (i.e. inequality along racial lines in the developing world; inequality and economic instability in the developing world due to monocultures created to serve Western demand).

In the course of explaining the phantasm that arises from these fears, Butler lists other phenomena but these are the main ones – as, presumably, are the spectres of collective effort and collective belt-tightening, which Butler says less about – that prompt those on the Right to reject any serious consideration of solutions and fixate instead on trans people who are second only to recent immigrants as a target for violence and media ire.

One minor frustration with Butler is that she does not offer the detailed accounts of intersectional activism and specific strategies for resistance that Naomi Klein presents in her series of books focusing on the environmental crisis that the Right refuses to confront (This Changes Everything, 2014; No Is Not Enough, 2017; On Fire, 2019), ending instead with a more abstract appeal for solidarity and a retreat into academese and academia itself. It can’t be held against Butler but it’s notable that she doesn’t write from first-hand experience as a parent in a world where the future is running outnor does she write about the second-hand experience of trying to parent at a time when misinformation is rife and hence it’s so much easier to fall into traps that cause you to harm your children (as Klein does in her most recent book, Doppelganger (2023), describing the abusive practices adopted by parents of neurodivergent children, in the hope of conditioning them to simulate normality, practices which have so many similarities to conversion therapy for LGBT+ people).

Evolution’s Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People (2004) by Professor Joan Roughgarden

Evolution’s Rainbow (2004) is a celebration of diversity in animals and humans. As a distinguished evolutionary biologist, Roughgarden challenges accepted wisdom about gender identity and sexual orientation, takes on the medical establishment and even Darwin himself, and (in a lengthy appendix) identifies positive representations of trans people in The Bible that fundamentalists urgently need to read to counter their claims of Biblical authority when invalidating LGBT people. Briefly, her discussion of diversity in gender and sexuality among fish, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals, including primates, explains how this diversity develops from the action of genes and hormones and how people come to differ from each other in all aspects of body and behaviour. Over 20 years on, pseudo-science and oversimplifications pervade anti-trans discourse from governments (in the UK, US, and elsewhere) down, so it’s ever more vital for non-scientists to see how normal non-binary genders are among animal species, the many alternatives to XX & XY chromosomes, and the existence of gender-fluidity.

(On a personal note, my chosen name, Kay, is partly a reference to the group of mammals to which we all belong in which same-sex attraction, old age, and infertility are no barriers to contributing to the survival of the species through nurture of the young, a sadly-little-known category that invalidates the arguments of bigots everywhere, including those who treat older women and those without children as invisible or less valuable.)

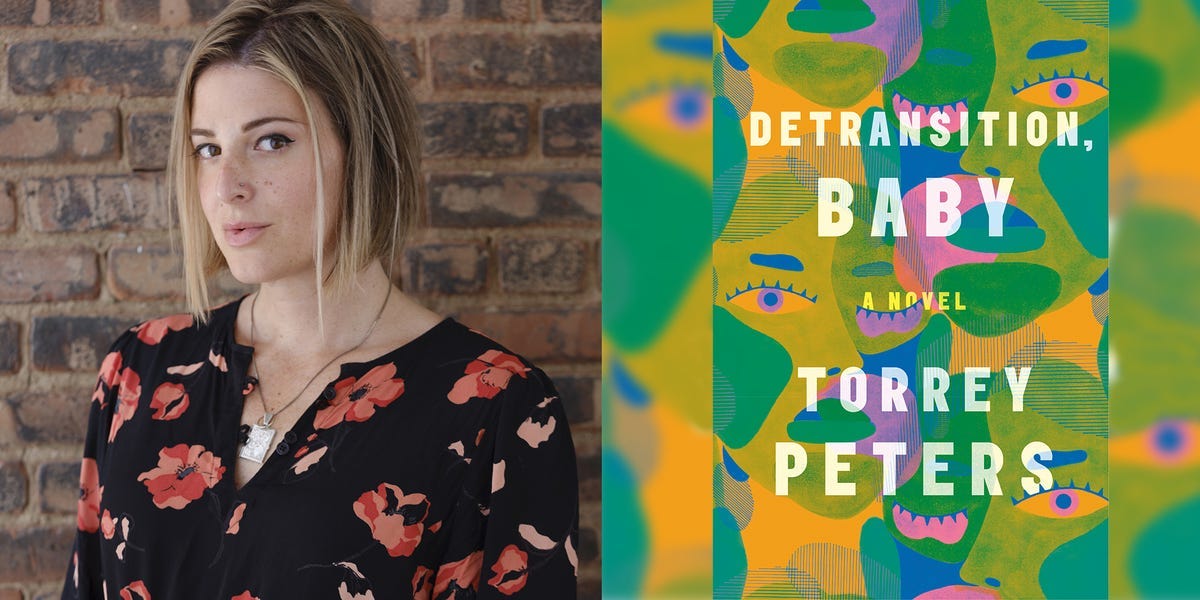

HONOURABLE MENTION: Torrey Peters, Detransition, Baby (2021)

Peters (b. 1981) was the first (known) trans woman to be longlisted for the International Women’s Prize and her novel appears here because while it is primarily a thought experiment about what comes next for trans women after we transition, “go stealth,” and manage to enter moderately respectable professions other than sex work (as so many still do in the Developing World and a large proportion did in the Developed World well into the late 20th century) - there’s a deeper awareness of the context in which these comparatively privileged women live, and why it’s so unclear where our lives are going. Do we detransition because it’s all a little too difficult… or have a baby (i.e. follow the cis female metanarrative)?

Peters imagines a new kind of queer family arriving that challenges the primacy of the bourgeois cis-het model and weaves some highly thoughtful discussion of trans politics around a popular premise, almost designed to infiltrate bestseller lists by spelling out parallels to the experience of divorced cis women restarting their lives in middle-age. (As the writer on this list closest to my own age, I’m moved by her notion of millennials as “angry elephants” who go on rampages (by analogy: angry and counterproductive tirades on social media) because many of their parents (i.e. queer people who were adults in the 80s & 90s) were killed by poachers-qua-AIDS, and hence unable to educate them in activism and community-building.)

Her main characters feel a bit more motivated by sexual fulfilment than self-actualization of an inner gender identity (perhaps for the sake of more dramatic tension), which raises the question of how much our traumata lead us to emotional and sexual edgeplay, but Peters sketches a range of transition narratives alongside the two main ones, drawing on lived experience, making this a valuable supplement to 21st century memoirs like those of Jacques and Plett, by comparing the differing experiences of people by class, age, and ethnicity. She also provides ones of the few depictions of detransition that feels authentic, which is increasingly valuable at a time when “right-wing grifters” (as Matt Bernstein, Natalie Wynn, and others call them) monetize their own detransition with backing from anti-trans movements, determined to paint all transition as harmful.

The novel is available for free at www.transreads.org as are above-mentioned works by Shon Faye and Gleeson & O’Rourke, as well as other articles by Serano and Stryker, and Gender Euphoria: Stories of joy from trans, non-binary and intersex writers (2021), ed. Laura Kate Dale. The title of this last text speaks for itself, presenting a vital corrective to the common notion that we are defined by our gender dysphoria (or: being trans is synonymous with feeling acute distress). While we should not conceal the difficulty of trans lives, gender euphoria is very real whether it comes about because one simply changes presentation (improving perceived quality of life better than anti-depressants according to numerous studies), starts hormones (which can further reduce mental health problems), or has gender-confirming surgery. The multi-author anthology also makes the powerful point that we vary enormously in our gender expression within cultures let alone across them.

[1] I.e. there’s nothing by Juno Dawson, although I warmly recommend her non-fiction to teens and parents of teens, including The Gender Games and What the T?

Wow. You really laid out a lot here and it's greatly appreciated. Just want to let people know that some of these books are available on audio. Amazon audio books (Audible).

[Yes I realize some people don't want to patronize the Amazon website or companies. But if you do, these books are available].

Also, I prefer to curl up with a book on my tablet and read on a quiet Sunday afternoon. But that's not always practical. So audiobooks may be the answer for some people. You can listen while you're preparing dinner or doing housework.

I just finished the Shon Faye book a couple of months ago. And right after that, I started the Stryker book. They are both long books and maybe good candidates for listening rather than reading. I need to get on the Serano material as a priority also.

omg I’ve been wanting to read some more academic books on trans-ness ; this is awesome !! I was wondering if u have any more recs of memoirs of maybe trans men ? if not no worries !!!