Travelling Overseas as a Trans Woman (August, 2024)

So far, the focus has been cultural forms in different media, but this piece shifts to how trans people interact with entire cultures and cultural spaces, and I hope to have more as we go on

Part I: Copenhagen, Denmark

It’s exactly three years since I learned I could do this – start hormonal transition – and I’ve come to the City of Very Tall Women for my first time abroad, presenting as me.

A less timid soul would have travelled to a place where the Holy Book says “Men should not behave like women” in one sura nor “...alter the body Allah gave them” in another. (To be fair, a third sura trumps these: that we should support every brother and sister whose only sin is against her- or him-self.) That less timid soul would be my companion of whom I'm more than a little in awe because that’s just what they did, a year before, travelling to Istanbul to see the mosque (and former church) that shares their chosen name.

But I've not come in search of the exotic; instead, I've come to a place that feels more or less like a remix of home, five or ten years into the future for being a little more clean, a little more civil, a lot more progressive when it comes to LGBT rights; as ever, trying to step out of the flow of Time to see where we're headed, to glimpse a better future for my siblings and me.

Two years ago, I ended my first Summer out by visiting my best (cis) friend in Madrid. Yet again, I find myself in the National Art Museum of the country in question, engaged in ekphrasis of the artworks, although this time I’m not high on recently started hormones, but essentially still in boymode, I’m floral AF in a pretty dress with orange, blue, green, pink flowers, and bold red lipstick, while my travelling companion wears an ankle-length, empire-line dress, forest-green with a white flower-print. We both look slightly prim compared to the next-most-fem person in any given room but it’s also an assertive, conspicuous femininity that feels mildly transgressive to flaunt in a space that screams “Kulchur!”

Almost immediately, I halt before a painting of the Archangel after whom I was named – or deadnamed, as it were – although their gender is dual, being the demiurgic aspect of God. I've taken photos of versions from museums and churches all over Europe but this specimen is especially magnificent in their black scaled armour with gold edging, standing over their old adversary, the dragon Unreason, whose scales are also black, and whose underbelly a pink that’s almost gold with swollen human dugs (just the two, ballooning impossibly upwards), while holding the scales of Justice in which two homuncular figures are being weighed. In no previous picture have I seen such a doubling of colours as if to say: what lies beneath the armour of Reason & Righteousness is a similar chimera, the androgyne concealed.

This time I find myself drawn to the exceptions. For all the motifs I've seen a dozen or double-dozen times, my favourite discovery might be the picture of a beautiful blonde-haired child of indeterminate gender, riding a shell in the style of Botticelli's Venus, but instead of a pearl s/he's perched on a bubble, and blowing others gleefully in her pink tunic that's blustering in the breeze against a blue sky with white cumuli. I've already forgotten its actual title in favour of my own – Allegory of the Precarity of Transness – and this is how we greet each one: with affectionate mockery born of real love for the Old Masters (and occasional Mistress) of the Renaissance, we who have been locked out of so much history but see traces of ourselves everywhere we look. In the sculpture gallery, we'll pause before Mozart as a child holding a violin as if it's a guitar and I'll murmur "Young Amadeus was a prodigy on the piano but it's less well known that, when it came to strings... he was a complete moron."

When we come to Joan of Arc (still long haired and in peasant dress at this point in her story) we delight in the way her up-rolled eyes seem to say "You want me to do what, God...? Really? The haircut I don't mind but...lead an army?! Isn't there someone else better qualified?" A little further on is an equestrian statue of Joan in armour, again looking heavenward, with pursed lips, as if to say "You're sure? There's still time to back out, you know..." Joan gets this treatment because she's one of Us. Not trans, for certain, but the epitome of all those who are called to do something ludicrous even if it means being burned at the stake.

But there's reverence, too. I turn away quickly from "The First Murder" having already scorched it on my retina. Here, a leonine Adam with gritted teeth and clenched jaw holds the body of his son as Eve bends low for a kiss. In the composition I see the necessity of the two ends of the spectrum for all my aversion to the idea of a Binary. I feel Adam's gritted teeth and clenched jaw behind my own face, holding back tears, and note the wide-legged stance despite his musculature, signalling the weight, in every sense, of his burden.

The boy is the bridge between them: the mother whose breasts are close to his head as she stoops for that kiss reminding the viewer he's still close to the age at which she last suckled him. All three figures form a triangle of dead space, being carved from a single block of marble yet it might as well be icing sugar there's such softness to those limbs, dangling. This is the primal scene the artist wants us to picture whenever we hear about a murder: the image of the mother and father who will always have been bereaved; the fact that the father carries the weight, too, no matter how stony faced; the fact that we are all one body.

I'm reverent, too, before a bust of Ophelia, much as my friend and I like to joke about her lover, the Egg Prince. Here, on her head, is the most exquisite garland of flowers ever carved out of stone, and her expression exactly demarcates the border between angelic and insane. Here is a mind broken by grief but quietly, beatifically certain she's going back to her One True Mother who will never desert her, whereas all the men in her life sought to control her. This is what art is for: to crystallize or set in stone those psychodramas we most need to see enacted in their purest form.

And whether we're in some whispering gallery or shade-dappled garden, I know now that I feel more present among these works of art than I feel envy for being apart. Envy never struck me strongly in galleries, before, since the styles are too fussy and the social roles too constricting but I also felt like I was in such places because I was in flight from the present. Now that I inhabit my body, I feel almost like a work of art or act of continual creation. Not artifice – as in the bigot's sneer that we're parodies or travesties – but something made by a benign god/dess that we, the Chosen, get to finish as if we're eternal students in Their atelier.

This is how we move through the human world and all those attempts, in Art, to take us away from our time, or preserve an idealised version of another time. But we have a strong compulsion, too, to get closer to the natural world, whether we're running our hands over the soft leaves of leucotrichophora, or leaning into the trumpet of a tropical flower, or climbing high into the branches of a tree in the park behind the Museum that is a work of Art itself, a page from the First Book as the Kabbalah calls the World.

One of the best things about the trip is to not just be out as myself but one of two people presenting femme, having had the one trans acquaintance I was aware of in my 20s and precisely zero in my 30s. I'm inexpressibly glad they’re here with me in these galleries and cafés, while I’m wading calf-deep in the sea for the first time while wearing a skirt, on a day that I feel certain I've arrived, and can't see anyone else in the mirror other than a girl. All I ever planned was to inhabit my body before I go, and yet I've found myself walking hand in fearless hand with someone who made the same journey as me, and now I'm glad I've had a second chance at life because I want to walk through all of history with such fearless friends at my side.

Part II: Vienna, Austria

It’s the orderliness you notice when you first fly in. Unlike England’s random patchwork of fields, a fool’s motley following the contours of streams and hills, a sort of rambling conversation with Nature over the centuries, the neat rows of Austrian fields are an “expression of imperial power” (I think) providing the manpower to tame the land, and to bulldoze old boundaries between neighbouring tenants, and it’s a phrase that recurs numerous times in my mind over the next 48 hours.

I’ve come to Vienna, this final weekend of Summer 2024, to visit my oldest friend. This will be my first time travelling solo, presenting as me, hence the euphoria is off the charts although it could so easily have gone a different way. The plan is to make an album employing excerpts from my transition journal, started just over two years ago, but it occurs to me that this particular friend may have unlocked one of the doors to my queerness 28 years ago, when they turned up at our 400 year old school – where we were both scholars, neither of whom could afford it, otherwise – wearing full Goth attire: leather trousers, black-dyed shoulder-length hair, and a tight black T-shirt, a lot like The Crow. This was someone who’d taken a Greyhound bus to San Francisco, solo, aged 15, on a pilgrimage to see the Spiritual Home of the Beats. Over the next two years they emboldened my small group of friends to paint our nails to match our jet-black suits, sneak out of school to go clubbing late into the night, all Gothed-up (that classic trans gateway), and return at dawn to sleep on a chapel pew (because my friend happened to have the key, being the organ scholar). Later, the two of us travelled abroad to drink absinthe out of pewter-lined skulls in a former morgue whose seats were coffins with one side cut out. When I turned up at university in black velvet shirt and trousers I was unconsciously channelling my friend, and also, it turned out, inviting queer girls to dress me up in their own clothes on the flimsiest of pretexts. But now I’m getting sidetracked.

To say that Vienna feels staggeringly beautiful (it does) is to almost immediately have to pan out, and upward (a crane- or helicopter-shot in the mind’s eye) to the larger historical context, just as the excitement of being here as a transfem, unchaperoned, prompts me to check my privilege (which isn’t some 21st century affectation, but a habit I’ve had since the early 90s when I couldn’t ever feel fully at ease with my education taking place inside a former monastery, built at the peak of the Baroque, even though I was one of its highest-achieving, most-highly-strung students). What I’m trying to say is: I’ve been programmed to see Vienna as beautiful ever since I started learning Latin at 8 and started my tradition of making an annual pilgrimage to the Royal Academy at 14. Vienna, after all, may be the most faithful facsimile of the Greek and Roman empires without the pollution and grime of present-day Athens and Rome. Every gallery I’d been to – and every Phaidon book on my shelf, every lesson in primary and secondary school where frustrated academics told us the origin of each mathematical theorem or scientific principle – pointed toward Vienna as the apex of civilization.

Which is why I’m in the city of Mozart, but also why, being a contrarian, I’m discussing an album of minimal drones in a restaurant immediately adjacent to a museum dedicated to the man. My foremost association with the composer isn’t any particular piece of music so much as the pseudo-scientific idea that there’s a causal connection between listening to him and academic attainment. There isn’t, of course, and it’s become a classic example of correlation rather than causation since parents who raise a child to enjoy Mozart tend to raise high achievers. Furthermore, subsequent studies have shown that if Metal is what relaxes you, it’ll get you into a suitable state for study just as well as Mozart, but neither really helps since you’re not actually in a state of flow until you’ve tuned the music out. This is where everything actually gets written – the state of flow – or channelled from the Elsewhere, your humble author more of a stenographer when the Muse starts singing.

Despite the ubiquity of Mozart in souvenir shop windows it doesn’t cross my mind to give him a listen over the course of two days, any more than it does to see an original Klimt in any of the galleries in the Museum District, despite the number of times “The Kiss” is replicated in plates, postcards, or fridge magnets. There’s an exhibition of Egon Schiele, too, an old favourite from my late-teens when dysphoria really started to sting and I would have said he articulated the feeling best of all if I’d had the language to do so, in the 90s, but I ignore him, too. The fact is: the “artist” I spend most of my time thinking about over the course of my 48 hours in Vienna is Adolf Shickelgrueber. Morbid? Maybe, but these intrusive thoughts are the outriders of a low-level anxiety that’s entirely rational – because I’m walking around a foreign city late at night, full femme, less able to gauge the threat of any passing stranger than I would be in London – and mostly overwhelmed by the joy of being here.

It’s been 101 years since the Nazis attacked Magnus Hirschfeld’s clinic in Berlin, hence I’m alert to any hints that the spectre of Nazism might be haunting Mittel-Europa, in the present day. And this is why I simultaneously celebrate and check my privilege with every step. I’m blonde enough to have been addressed in Danish in Copenhagen, and in Swedish in Malmo, hence it crosses my mind at Vienna airport I’m not just looking “Trans Goals” but “Aryan Goals,” before my Super-Ego hastily punches my inner Nazi down into my unconscious for thinking such a thing. In many ways, this is the least brave journey I could have made and despite my wariness of packs of young men, after dark (and older white women who might be TERFs, in daylight) I never for a second feel my heart skip, my throat constrict, or my guts clench.

In the past 12 months I’ve had more CPTSD attacks than the rest of my entire life (which may be close to zero) and the causes have been many – the rise in violence against my siblings, and our increasing suicide risk; the actual suicide of a student at my school in my first term; the threat of my separation from my wife to my children’s (and my own) mental health – and yet the trigger has never been a sense of immediate threat to my own life. In the poorest parts of London, late at night, I’ve never felt more alive, and the same is true in this foreign city. What this says about how much I value my own life I’ll leave you to speculate but I think it’s valid to suppose that the greater threat I feel is to those unknown, closeted kids at my school going through the wrong puberty, exhausted by masking every day (at best) and afraid of violent attacks should they be discovered (at worst).

But I’m about as safe here as I’ll ever be. In Vienna, obedience is so ingrained you’ll see citizens stood at a crossroads at midnight, nothing visible the length of either boulevard, but still they wait for the lights to change. No-one tuts when I jaywalk and I’m not sure if I sense or merely imagine their disapproval. Perhaps it’s so inconceivable anyone would jaywalk they simply can’t see me, can’t process the sensory data that fits with no conceptual schema available to the Austrian mind. Perhaps the same goes for my being trans, although they might not let the mask slip either if they clocked me as such. Recall the words of Joseph Fritzl’s neighbour: “He was a very thin man but always had so many bags of shopping, but I never asked why” (i.e. to feed the secret family he kept in the basement); likewise, his lodger: “The electricity bill was higher than anyone else on the street but we are in Austria where it is impolite to ask questions or complain.” Indeed.

My first fix of culture (other than soaking in the warm bath of ecclesiastical and imperial architecture and sculpture as I stroll the streets) is, of course, the Freud Museum. A quarter century ago, I read the collected works cover to cover, all 14 volumes, in search of any passing reference to what was, in his day, ‘Psychopathia Transsexualis’ (after Krafft-Ebing), and one result was that I still view most cultural phenomena through a Freudian lens, which isn’t to say as an expression of repressed sexual desires but: signifying according to the mechanisms of condensation and displacement. The Freud Museum does just that: it asserts the vast cultural importance of one man, a Jew, and condenses Psychoanalysis into his person and home, while it’s the stairwell inside the block of flats (not a blue plaque outside, or a monument) that constitutes the only Holocaust Memorial I’ll see anywhere in the city, by contrast with more public ones in Berlin or Amsterdam. On the walls of the stairwell is a list of all the residents in the building with the names of the KL to which they were deported, and their specific fates, whether death by disease, or starvation, or Zyklon B. The Freud Museum might epitomize Viennese intellect but the hollowness at its heart contains the atrocity, as if to suggest that Psychoanalysis could have contained it, given half the chance. Then again, Capitalism proved itself capable, in the long-run, of containing Psychoanalysis and as has often been observed, Freud has a greater influence on Madison Avenue than anywhere else. A chalkboard on the pavement outside the Freud café has a very Austrian joke: “Lustprinzips: Pink Lemonade” which translates roughly into: “Obey the Pleasure Principle: have a drink!”

Vienna might have been the heart of an empire hence its enormously conspicuous display of cultural capital, imported from all corners of the globe, but there are also little signs of progress creeping in. Outside the Natural History Museum are statues representing the continents whose sweat produced all this wealth: ‘Europa’ is a seated Statue of Liberty with spiked crown, chaste toga over bomb-like bosom, gazed upon by her young male lover, fawning with his lyre, and chin propped on a camply folded wrist; ‘Amerika und Australien’ is a jaw-dropping racial stereotype: the heroic brave with a feathered spear and bear-claw necklace, with a surly, wide-nostrilled, heavy-jawed Australian Aboriginal woman seated at his feet, bare-breasted (unlike Europa) but ignoring the child clinging around her neck. Arguably, it’d create more controversy to remove such statues, so it may be better to have the correctives that are the exhibition of Avant-Garde Art of Africa and the Diaspora, at MuMoK (Das Museum Moderner Kunst), just a few minutes away, elsewhere in the Museumquartier. Some of my favourites are the paintings based on album artwork for classics of “Fire Music” (the Free Jazz of the 1960s consciously articulated to the revolutionary spirit of the times). In the same gallery are prints of fantastical creatures using inked up body-parts of a genderqueer artist celebrating their cultural and sexual liminality by defamiliarizing the body in ways that are playful and monstrous at once.

The Franz Joseph building has nothing to apologize for in its statuary (unlike its namesake) but wears its own signs of modernity: a poster for the Rocky Horror Show hung in one of three arches above the foyer, alongside a programme of modern and classical dance. (It reminds me of the cathedral in Moscow that was turned into a bath-house as a deliberate act of sacrilege and overt atheism, under the Soviets, before being restored to its Orthodox glory: this, I think, is what the TransLuminati would do if we ever actually took power… although this is the same month that our ludicrous former prime minister, Liz Truss, claims we already have.) A library I’d passed earlier, in red sandstone but with a mock-Parthenon frontage (a pantheon of muses in the triangular frieze above the columns), has a Progress flag, two-storeys-high, hung in front of the reading room window, as if held by the cherubs leaning on the top of the arch. In gold letters above that: ETABLISSEMENT. If only.

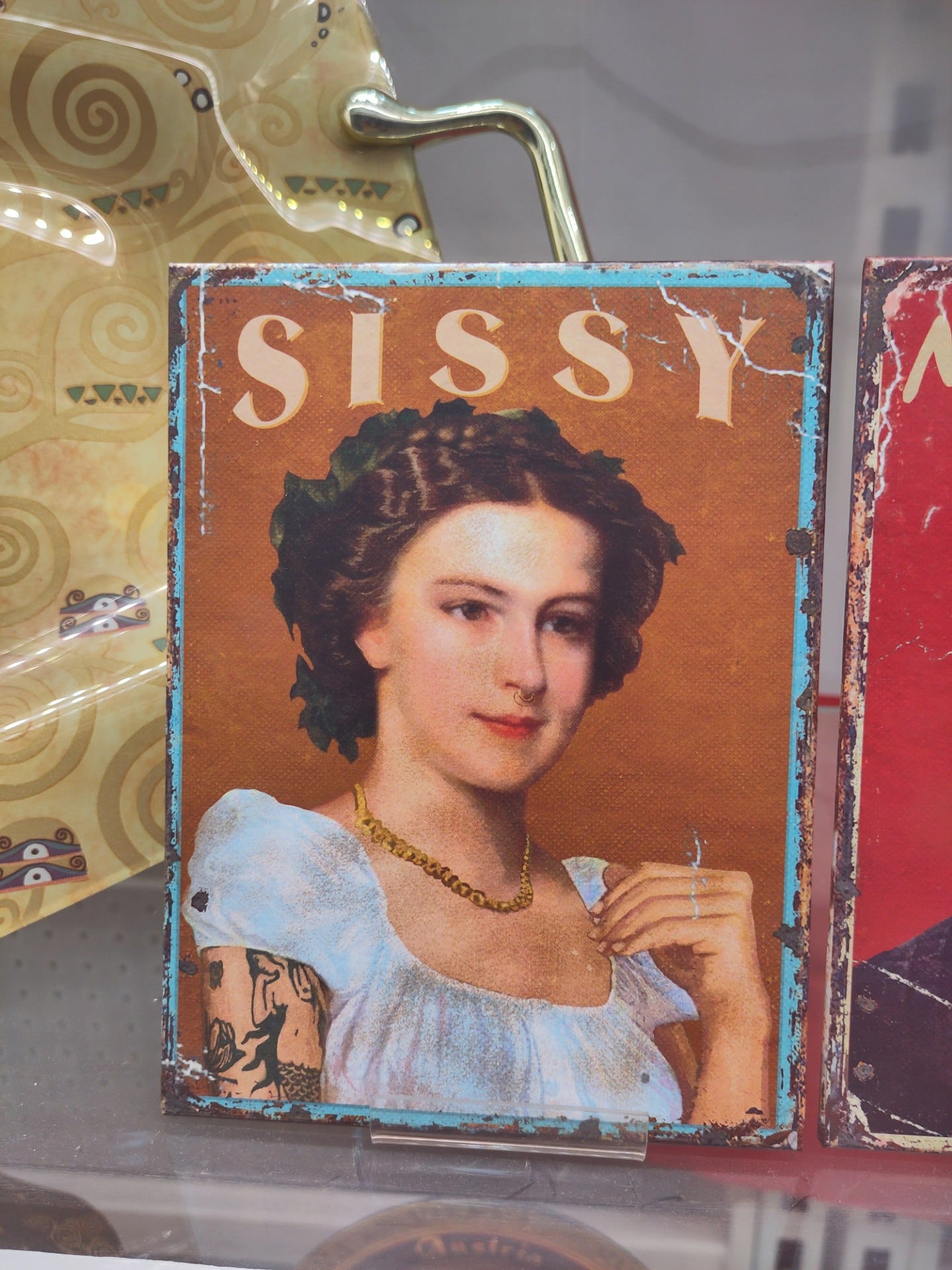

In the window of yet another souvenir-shop I see one of thousands of images of Vienna’s favourite fashion icon, “Sisi” (the Empress Elisabeth of Austria, of the House of Wittelsbach); this time, her name is spelled “Sissy” and her image has been doctored so tattoos appear on her upper arms, below the capped sleeves of a white silk dress. Next to her, there’s the dorkiest image of Mozart I’ve seen in my life somehow accentuated by the leather-jacket that’s supposed to make him punk. I don’t know if there’s an intentional echo of the transfem subculture that celebrates hyperfemininity and infantilization (often going hand in hand with BDSM) but I like to think someone’s smuggling it into the mainstream (rather than that capitalism is co-opting this, too).

Ultimately, I can’t tell whether this amounts to insincere virtue signalling or a proportional representation of queer culture, permeating a place that – by virtue of its imperial past – exported the gender binary that so often went hand in hand with Colonization, around the globe, and all its systems of not-so-fun bondage. 48 hours isn’t enough to condemn a culture or excuse it and praise it for making amends. As an amateur anthropologist, I know that one has to be embedded in a place, ideally engaged in participant observation, to begin to attempt to evaluate a place, which is why I can’t say whether Denmark and Austria (or just their capitals) are genuinely progressive or sufficiently wealthy and politically stable that I didn’t glimpse any of the trans- or LGBT-phobia that spills out when there’s deep structural tension between the exploiters and exploited, displaced onto vulnerable minorities.

It took me a full month to figure out an ending for this piece, the day after reading a statistic in PinkNews that ‘More than Half of Same-Sex Couples Are Scared to Hold Hands in Public.’ This Spring and Summer have been the first of my life I’ve even had the option of holding hands in public with anyone of the same sex or gender-presentation, as well as hugging and kissing, so I’ll end on the thought that it’s been immensely healing and you can almost quantify the importance of doing so, by considering that figure. I didn’t just hold hands in Copenhagen – I swung them, grinning like an idiot – whereas I couldn’t dispel thoughts of Hitler in Vienna… but at least it wasn’t fear. I’m no longer feeling fear.