Twin Peaks as Trans World

This article was started at the turn of 2025, two weeks before David Lynch died, at a time when I was processing an enormous amount of loss and fear for the future, yet I haven’t altered the tone or content in light of David Lynch’s “return to the Other Place” as one of his collaborators put it. He was and is my favourite Renaissance Man of the late-20th and early-21st century, in a league only with Brian Eno and (why segregate by gender?) Laurie Anderson. In these circumstances I tend to feel more gratitude than grief: a hero of mine reached old age with an extraordinary body of work that will live on, stayed true to his vision right to the end, and managed to articulate the ways in which we mortal, meat-based beings can nonetheless step outside Time, which was one of the core projects of Surrealism in its original incarnation. Even his most neglected or maligned works – Dune, Fire Walk with Me, and The Straight Story – continue to touch me deeply as they did in my teens, and while I cannot easily fit them to the argument here, these too offered clues how to live, and to reconcile myself to masculinity and male embodiment when I was struggling to survive as a closeted trans woman, almost certain (from my many experiences of violence and isolation) that transition would be a death sentence. Lynch may have only offered clues, I stress, and not always answers, but presenting life as a wonderful mystery is better than pretending to have a solution.

To start with the basics, Twin Peaks is a small town in the Pacific North-West on the edge of the wilderness, where an investigation into the murder of Laura Palmer – high-school prom-queen, daughter of a prominent lawyer, girlfriend of a star football player, volunteer delivery-girl supporting elderly and disabled shut-ins – exposes the dark underbelly of the town and by extension America itself in the Reagan/Bush Sr. era. I’m not going to spend a moment proving that the two seasons that ran from 1990–1991 established it as one of the most influential TV series in the English language of the last 40 years – please just take this on faith, google that claim to find other articles backing it up, or check out luminaries like Greil Marcus on the subject. (Since I wrote this paragraph in early January there are dozens more.) Instead, I’ll briefly focus on how it manages to transcend the trashiest of genres and arguably attain the status of high art, before developing my analogy to Trans World. If you’re only now catching up, you need to know about this, trans or otherwise, but if you think you already get it: keep reading.

One key aspect of the first two seasons is that most of the major characters are in love with (or having an affair with) two other people; in this respect, Twin Peaks might sound like a satire on soaps at their silliest (and, Yes, there is a high camp TV series-within-the-series as a way of winking at the camera) but the creators David Lynch & Mark Frost seem to have found an emotional truth in the premise and do this to foreground the fact that we all hide something of ourselves so as to function in society and, as the affairs unfold, characterization itself often shifts from the ridiculous to the sublime: we see the staid façade contrasted with the yearning, passionate, sometimes damaged inner self. (Yes, even the Andy & Lucy & Dick plotline.) Psychoanalytic readings aside, this is a way to explore the interdependence of individuals despite different socio-economic backgrounds, genders, and sexualities in keeping with literary Realism (when it emerged in the 19th century, panning out from the aristocrats formerly at the centre of classical drama and poetry), albeit with a distinctly 1990s emphasis on desire and hedonism at a time when cocaine was the drug of choice for middle-class high-school students, and heroin (only for the most villainous, here) had a double association with danger for being regarded as a vector for HIV/AIDS.

In Twin Peaks anyone however apparently Straight / Vanilla / Morally Upright can have a hidden side, whether they frequent the upmarket casino-cum-bordello One Eyed Jack’s (above), or the downmarket Roadhouse / Bang Bang Bar, mingling with the criminals importing and selling drugs in the town. Some of the sex procured by the shady- and superficially straight-world citizens alike involves kinks and fetishes; some of it borders on pederasty; even in bourgeois homes, some of the sexual encounters have a distinct note of violence or masochism. Anyone thinking the sex or drug-use is part of a general vibe of weirdness “pour épater la bourgeoisie” isn’t watching closely: if we focus on Laura alone, it’s clear that her foray into sex-work was partly caused by her addiction and this, in turn, was a response to frequent sexual abuse starting in childhood. There’s a compassionate attempt by Lynch & Frost to reveal the factors feeding into what the Religious Right in Reagan’s America would simply denounce as Sin; that said, they don’t let Laura completely off the hook: she sought to corrupt her boyfriend Bobby, her psychiatrist Dr Jacoby observes, by encouraging him to sell drugs because she considered herself to be corrupt, and we have to ask whether she could have broken the cycle of abuse. Her work delivering food to shut-ins suggests a longing for atonement and redemption, and one tragedy of her death is that we can’t know if she managed to feel much hope of achieving it before her life was cut short.

It’s harder to parse other instances of kink or fetishism in the series but a general observation can be made about Lynch’s greater body of work: that sado-masochism (epitomised by Frank Booth & Dorothy Vallens, above, in 1986’s Blue Velvet) is morally ambiguous, never just a proxy for sleaze (let alone evil), and women are shown to be capable of inflicting violence and enjoying violence alike as a way to realize their self-control or tacit control over men who may have less control over their own instincts, or less understanding of how women control them to fulfil their desires for pleasure situated away from the genitals, and not confined to the “phallic arc” from stimulus to explosive but short-lived response. (See also: https://www.businessinsider.com/blue-velvet-kink-as-healing-from-trauma-opinion-2021-11)

You may feel, already, that we’ve been stepping further downward into the criminal underworld as this synopsis continues, and simultaneously into the unconscious as locus of repressed desires, which would be more or less correct, but what makes something distinctly Lynchian is the introduction of a supernatural element that might be assumed, lazily, to “defamiliarize” all of the above (i.e. to make us look at ordinary experience more closely by mobilizing metaphors and symbols). More than that, I would argue, it captures the emotional truth of how it feels to reach extremes of human experience: to be on the edge of the wilderness or the frontier (that potent, quintessentially American trope) whether of sexuality, morality, criminality, or different forms of masculine and feminine embodiment. This has been my own experience (and other people’s) of times when my (our) life has been seriously threatened, or even just my sense of the viability of my worldview or way of living: I’ve seen things that weren’t literally there (as have others), I’ve imbued events that certainly did happen with profound significance (because the alternative is to be overwhelmed by the apparent injustice and meaninglessness of existence), perceived people as if they were archetypes or (temporary) avatars of something otherworldly rather than individuals, and I’ve spotted patterns that may well be there, whether or not that means there’s some externally imposed or pre-determined purpose to it all. Lynch’s body of work proves nothing about the existence of higher powers, it should go without saying, but the enduring fascination of his work proves our need for them, at times, and his ability to articulate emotional truths about what it means to be human, through the strangest of fictions.

The town of Twin Peaks, we discover toward the end of Season One, has a mirror-world known initially as The Red Room (echoing the name of the place where Bronte’s Jane Eyre first confronts her fears at their most supernatural before her abusive guardian ships her off to a school run by an abusive and hypocritical religious figure where conditions are so poor they contribute to the death of Jane’s closest friend, setting in motion a compulsion to repeat her traumata in relationships with highly problematic older men). Lynch’s Red Room is later conflated with The Black Lodge of the mythology of the indigenous people of the Pacific North-west, and some of its inhabitants seek to possess vulnerable mortals; most notably, Laura’s father, who we learn in one of the most famous denouements in TV history, had been possessed by the lupine Bob (with his long mane of grey hair, manic eyes, and wide, teeth-baring snarl), although Leland also provides the audience with clues that he may have been abused by a literal, mortal Mr Robertson, hence “Bob” is a psychical trace of that original trauma that is so intense that our hero, FBI Agent Cooper, can sometimes see him as Leland does. The revelation that Leland killed Laura is notorious in TV history for reasons we don’t need to dwell on (pressure from the network… a dubious artistic decision that caused Lynch to leave for the middle episodes of the uneven Season Two) but we’re still talking about it 35 years later because it’s not fully clear what Bob is or wants or whether Lynch & Frost want us to believe that forces embodied by the likes of Bob exist externally, or as tropes for What May Lie Within Us All. Early in Season Two, a spirit called Mike (whose familiar Bob had once been) speaks through the One-Armed Man, temporarily weakened by drug withdrawal, to explain that he is a creature thriving on fear and pleasure; implicitly, with no capacity for empathy. Paradoxically, this reduction of Bob to something like the Freudian Pleasure Principle untamed by any Super-Ego, when delivered by a character implied to have been a wizard who attained certain powers through a ritual sacrifice, reminds us that the encounter with that which is most primal and bestial in our nature can feel like an encounter with a higher power; by definition, it is that which we fear we may never control, and hence feels godlike however organic its origins. This is the “surplus” of meaning that Lynch and his various collaborators (especially Barry Gifford, in Wild at Heart and Lost Highway) bring to their various symbols, as well as the plots that shift diegetic levels so that one has to watch carefully for when characters slip into some equivalent of a dreamworld, whether it corresponds to their hidden fears and desires laid bare, or a criminal underworld, or sexual demi-monde, where ordinary rules of morality don’t apply to such a terrifying extent they seem to damage the ordinary rules of causality.

Why does all this matter to me, as a trans woman? Why should it matter to you?

At some point after embarking on transition (almost exactly three years prior to writing this piece) I started to ask myself how certain books, films, albums, artworks, etc. would feel to me, whether they had once served as valuable guidance through the emotional turmoil of other transitions in life that I could re-apply to the present one… or as especially resonant depictions of (tragic) masculinity that I no longer needed… or forms of femininity that no longer gave me such painful gender envy that I could now bask in them and consider how to integrate them more obviously into my behaviour, appearance, ways of relating to myself, to others, and the world (although there had always been plenty of female role models I was able to quietly claim for my own, over the years, such as Bronte’s Jane Eyre, or McCullers’ Mick Kelly and F. Jasmine, even if it wasn’t obvious to others).

These projects are integral to what I’ve been doing with “Trans Perspectives in Culture” for the past 18 months, although I don’t want to limit it to these. The idea of revisiting Twin Peaks and seeing how I feel about it as a “full-time” or “fully socially transitioned” trans woman has been with me for a long time, just as I wanted to revisit the major works of Robertson Davies, which it might surprise some readers I did first because it involved reading almost 3,000 pages, rather than 36 hours of television. The fact is: I expected Davies to console me and convince me that life could have a sense of magic and wonder whilst being highly cerebral (as he’s done roughly once a decade since my teens), which I needed during a tough six months when my career crashed on the rocks of transphobia, while my mental health took a double kicking from the realization that once you’re deeply immersed in Trans World, there’s rarely a week goes by when you’re not seriously afraid for the life of someone you know, care for, or love (which I sincerely hope won’t be the case forever but does not seem like my own unfortunate experience but a disturbingly common trend).

Lynch I delayed approaching partly because there was a risk of triggering seriously painful memories of physical assaults with weapons, or sexual assaults (not of me but of former partners, plural), the emotional intensity of which would be unpredictable given that hormonal transition has increased my capacity for joy, but also my sensitivity to the suffering of others. It’s not that I was affectless before – the sadness I felt when I had male levels of testosterone in my system was well within the normal range, as was my anger toward perpetrators, fictional or otherwise – but I almost never found myself wrenching my eyes away from the screen, or gasping for breath, or my face contorted as if a meathook were pulling at the corner of my mouth, within seconds. Over the past 15 years I’ve taught hundreds of children and young adults among whom I’ve been aware of many victims of peer-on-peer violence, parental abuse, self-harm, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and at least two “completions.” There was always a danger Lynch would cause me to confront my darkest memories of primary and secondary traumata in need of further processing, but I didn’t expect Twin Peaks to become a lens causing me to view current events in my life as so utterly uncanny it was hard to believe I hadn’t stepped outside the ordinary world.

Twin Peaks as a mirror for Trans World

At the start of my 20s, with limited experience of relationships (although I’d done a bit of “gender-exploring”), the idea that everyone in Twin Peaks is in love with or having an affair with at least one other person… a lot of people are self-medicating for trauma with hard drugs… relationships often have sado-masochistic undertones… felt like ways to defamiliarize or foreground aspects of desire, gender, sexuality, and social relations that we would otherwise assume to be rare aberrations, somehow Other and marginal and abject rather than potentially latent in all of our psyches. What I realized the more I became embedded in Trans World in my 40s, was that the world I’d thought to be larger-than-life now felt more like a documentary or straightforward realism.

First, there’s the polyamory.

Now, I can only describe what I’ve seen among 20-40 year old Londoners actively participating in trans circles, and what people I’ve never met IRL discuss online, rather than among all trans people everywhere, in other demographics, but – Yes – it’s vastly more common than among all the cis-het people I’ve met in the Grand Metropolis, who tend to be liberal, left-wing, and indifferent to religion. Having said that, I want to hastily refute GC or TERF interpretations that we trans people (especially trans femmes) are all lust-crazed biological males, craving sex with anything that moves. Polyamory need not preclude asexuality and can serve to satisfy partners where libidos differ a lot, or for whom dysphoria (or HRT) makes penetrative sex difficult for one partner, although they may have similar needs for emotional and/or physical intimacy with others. In short: it’s hard enough to find a partner who pushes all your buttons in Cis World, but when you’re 0.5% of the population you may need to take your affection – or pleasure – where you can. Not to overshare but I was surprised, last year, after a quarter-century of monogamy, to find myself okay with a partner having strong feelings for someone else (and a measure of physical intimacy with them, as did I with someone else) because they so clearly give each other something I couldn’t without a lot of unnecessary pretending, and none of us make sense as each other’s main partner at this point in our lives (although the friendships continue to develop and I cherish them whatever might happen in the near or distant future). All of us have been quite isolated for different reasons and, no doubt, other people in Trans World have their equivalent reasons. Watching Twin Peaks at this point in my life, I picked up on Cooper’s mildly comic moments of spotting Who’s-Secretly-in-Love-with-Whom but if we view him as the epitome of a benign, born-again consciousness, alert to the beauty of the natural world, and compassionate to those caught up in the horrors of the human world (modelling a worldview close to Lynch’s own, as a practitioner of Transcendental Meditation), it’s more than a joke: it’s acceptance of what can sometimes be necessary (to stave off loneliness and despair), sometimes ideal (for complex people with complex needs but plenty of emotional maturity), and is rarely if ever a perversion or unambiguously immoral.

Second, there’s the drugs.

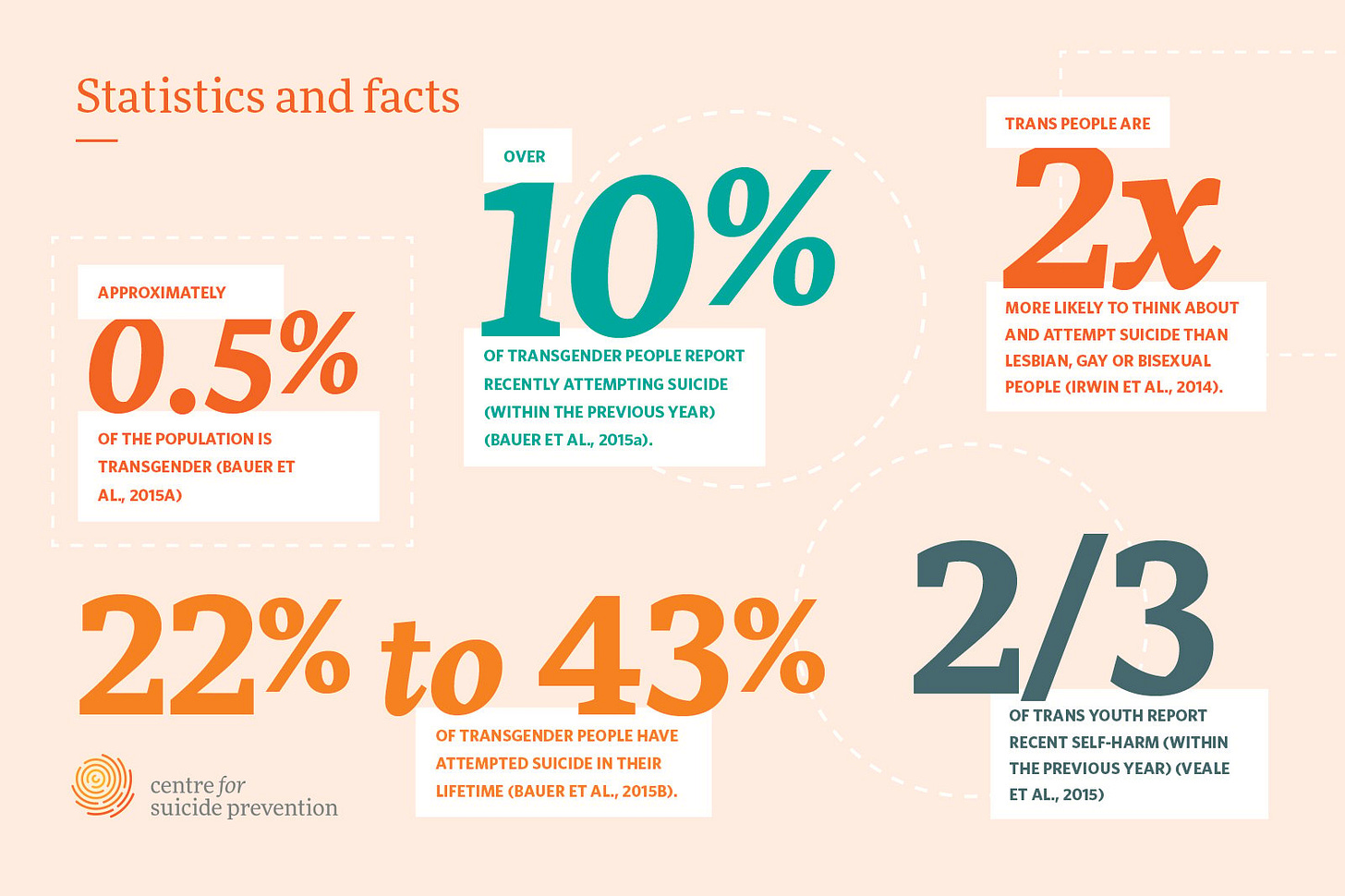

There’s only so much detail I can go into, of course, but I recall a trans event when the conversation at my own table, and a neighbouring one, concerned What medication one could take for ADHD or OCD or other conditions, and in what doses, without unpleasant interactions with ones HRT. Fair enough: sharing information about medication will always be an integral aspect of trans events (until we reach some utopian future akin to Iain M Banks’ “Culture novels” wherein we can will our implanted glands to secrete what we want, even inducing a change of sex…) and we do it for the sake of safety, self-actualization, reassurance, and often survival, rather than reckless rejection of professional medics’ advice, since the state of trans healthcare in the UK is so murderously inadequate. (FYI, cis-allies reading this primarily as Lynch-fans: the average wait for a first appointment with a Gender Identity Clinic is now 39 months, which is a fact that has been cited on coroners’ reports, plural, in cases of suicide.)

The aforementioned conversation then evolved into What recreational drugs one could take with HRT as well as ones medication for ADHD, and so on… Hmm. Here, we seem to have crossed a moral line… or have we? Yes, there was some bravado, as with any group of young people talking about drugs, but also a very necessary effort at harm reduction. Most trans people know that the hormones and blockers we take can have side-effects of varying degrees of seriousness and treat it with far more care than their peers who tend to assume their own immortality in their 20s and 30s, or that future-self can pick up the bill. Recall what I said above: at any given point, most trans people may know someone whose life is at risk. Conservatives may sneer at the notion of drug-use as “self-medication” for psychical pain or trauma but we trans people have these things in spades. A lot of research points toward Complex-PTSD being something to which trans people are especially susceptible (not least because one of the foremost causes is being in a hopeless, harmful situation for a prolonged period, with a strong sense that there are few if any people who can help or even be told… which is distinct from “classic PTSD” which tends to involve a traumatic event associated with a distinct place and time). Yes, trans kids are more likely to be bullied even before they’re out to themselves, but even the best adjusted in the 2020s are by definition trapped in an unpleasant if not hellish situation because they’re going through the wrong puberty in all but a very small proportion of cases. Unfortunately, CPTSD hasn’t been formally recognized, so treatment is necessarily private and expensive, or at the end of another long waiting list, with trans people often refused other forms of counselling more easily obtained (such as CBT) because our needs are deemed too specific. Lynch & Frost’s depiction of drug-use, now, feels all the more valuable for their compassionate attempts to understand the needs that some people have, even if self-medication for trauma can only mitigate the use of controlled substances partially, given the entanglement with other forms of crime.

Third, there’s the kink, fetishism, and S&M – let’s not muddle them.

Across the first two seasons and the prequel film, we see flashes of sadism and masochism alike in Laura’s character, although neither marks her as intrinsically good or bad (and I’m certainly not going to extrapolate from a 1990s TV series to behaviour among consenting partners in the present-day). She laughs at Bobby for crying after the first time they have sex… to pay for drugs she sells sex in a brothel where the clients are often much older and the girls barely legal… sometimes she engages in sex that involves high risk and degradation, e.g. the scene in Fire Walk with Me in the Roadhouse where the lighting is low and blood-red as she offers herself to strangers… the ambiguous line “sometimes my arms bend back” (delivered by a Double of Laura in the Red Room) suggests that some of this sex involved bondage or restraint… and she certainly was tied up just before her murder (hence that cryptic line could be interpreted as an allusion to her spirit, in the afterlife, reliving her death interminably, even if the specific trauma only happened once in life).

Why we can say that Lynch & Frost are to some extent engaging with the psychology of S&M rather than just deploying it (and other kink practices) as signifiers of “extreme behaviour” intensifying our outrage at her murder is because Laura is always shown to have some degree of agency, although we never know how much. Her high-risk repetition-compulsion is a response to extreme trauma (much of which happened when she was a minor) but she also sought therapy and performed acts aiming at redemption, and there’s also the possibility that she, like Dorothy Vallens in Blue Velvet, enjoyed some of it. In a crucial scene in the 1992 prequel Fire Walk with Me (depicting the events leading up to her murder) Donna joins Laura in offering herself to strangers an effort to save her and understand her but also, clearly, out of significant envy of the pleasure she sees her taking, when the more “morally upright” response would be simply to intervene. The basic insight is that there is pleasure in risk for everyone, in handing over or taking control, and this can be experienced by anyone with or without being determined by some intense trauma (which is largely lacking in Donna’s middle-class household, as the daughter of the town’s doctor, and both parents very loving albeit that we don’t know why her mother is in a wheelchair or how it affects her).

One-Eyed Jacks, the brothel where Laura briefly worked, is a place where we see the teenage Audrey (trying to impress and ultimately seduce the much older Agent Cooper) selected on the basis of her youth for a client who turns out to be her actual father (not just “old-enough-to-be-her-father”). We also see the kink of the middleman who recruited her to work there (being tied up, blindfolded, his toenails varnished, a sex-worker hoovering in the background, and something involving an ice-bucket that gets left to the imagination for comic and dramatic effect, just after Audrey’s been warned that this trussed up, supine man is nonetheless dangerous). Twin Peaks is far from a comprehensive survey of kinks any more than Lynch’s greater body of work might be, but it certainly seeks to collapse normative assumptions that activity and passivity – dominance and submission, sadism and masochism – neatly align with masculinity and femininity. Because of how we are acculturated to behave, there is always an erotic charge associated with transgression for all characters (including the moral centre of the whole, Cooper, who has to resist his attraction to Audrey). Lynch & Frost are careful not to victim blame – nothing that happens to the aforementioned young woman can be excused on the basis that they were “asking for it” – but they are also careful to show that risk is attractive for men and women alike of varying degrees of “well-adjustedness.”

At this point there’s not much I can disclose about what I’ve seen in Trans World without putting friendships, relationships, and my personal and professional reputation at risk. What’s factually true is: trans people are significantly more drawn to kink than cis; more likely to be in polyamorous relationships; more likely to have experienced some kind of abuse before or after they came out (from peers and family members); more likely to have experienced violence from strangers or intimate partners. [[1]] At this point, I’m certain that some of the appeal of kink for trans people is that a lot of us are coping with “bottom” or genital dysphoria, hence it’s healthy to treat the whole body as an erogenous zone, and explore a variety of sensations, and therefore it’s valuable for me (and other viewers) to have seen Lynch & Frost exploring the way that many people’s, if not everyone’s, inner desires exist on a spectrum of kink, regardless of their external appearance of respectability. It’s reasonable to suppose that once we trans people have broken one of the most pervasive taboos in modern society – adherence to the normative behaviour of our Assigned Gender at Birth – it’s somewhat easier and more tempting to break a whole lot more, having recognized that what is “Good” and “Normal” is sometimes simply what is Good for Capitalism (the gender binary, above all) and what is Normal is only statistically so but that doesn’t make it right (and what we assume to be Normal may, in fact, not be Normal but Normative).

I’m also aware (second-hand…!) that kink can be addictive, escalatory, lead to life-changing events, enable intimate partner violence by framing it as kink, and put people in situations that they might feel themselves to have consented to, at the time, but consent is simply not possible in a chemically altered state, and they may not feel violated until much later (e.g. during therapy). These are rather vague, general observations, protecting people’s privacy, but it’s also true that riskier kink practices are becoming much more common at a time when anyone can connect with anyone online, and stream footage of a vast range of practices, for free, that were “gatekept” by the cost and scarcity of specialist porn and erotica just 15 years ago. In the 2020s, teachers are now instructed to be aware that porn easily available to teenagers is normalizing choking (as one of the more visible phenomena) but what kink meant to my peers (turning 21 in the year 2000) was never anything that might prove fatal or life-changing, and the most extreme practice whispered about by friends was branding. What kink means to some (trans) people, now, absolutely can be fatal or life-changing, and I’ve lived with the very real fear that some of my siblings might kill themselves or be killed (by accident) because of what they’ve been into… even before we get to the issue that we’re more likely to be killed by cis people because of how we’re fetishised, objectified, and demonized by some members of the Press and politicians. (NB cis-allies, this isn’t just my view but that of the Home Office of the British government, explaining the 186% rise in violence against trans people over 5 years.) At the time of writing, I’m struggling to cope with the fallout of death threats against a friend, and I’m not the one on the receiving end.

As it happens, the day I revisit this article is the day after David Lynch died but it’s also the day after the sentencing of a group of young cis men and women who almost killed a teenage trans girl in revenge for not disclosing her AGAB before kissing and performing oral sex on one of the gang, and then only at knifepoint. This particular tragedy epitomises the risk we take when seeking any human connection. Over the last two years (having started HRT 30 months ago) I’ve gone to more dangerous places, in poorer parts of the city, associated with higher crime rates, simply for the sake of making friends or being in the comforting presence of other trans people (e.g. at a trans film night). The once strange and daunting has become familiar while the once familiar (Cis World) feels increasingly strange, and I actually feel slightly safer than I used to, presenting as me in public, partly because I no longer have the near-constant feeling of anxiety that came with having the wrong hormones. Like Twin Peaks as we progress through the seasons, Trans World has become more of a place I belong even while I’m more aware of what’s beyond the trees.

So far, I’ve traced an analogy that was surely unintended – and would likely not have felt as resonant if anyone cis set out to represent trans culture from external observations alone without dipping into unconscious imagery evoking the absurdity of our existence as gendered beings – but that’s not to say that Twin Peaks was without conscious trans representation.

I’m speaking, of course, of Agent Bryson, the transfem DEA agent played by David Duchovny in Season Two. We could pick apart her character and the choice of actor indefinitely, or cut through the Gordian knot by saying “it was the 90s,” i.e. a time when any trans character who made it to the finish line alive was a gift. That alone would be a big deal if she were a walking cliche in other respects but some aspects of her character seem indisputably positive: that Agent Bryson is accepted by those around her; that she’s attractive to at least one character without being a fetish object; that she figures as heroic in a crucial episode without seeming to exist to sacrifice herself for others or accentuate the heroism of the nominal protagonist at the centre of the plot – Cooper, a white, cis-het male – but simply assists as part of an interdependence of agents whose individual value and heroism may be equal or greater, which trans viewers might assume it to be, even more than Cooper’s, even if cis viewers would be forgiven for taking Duchovny’s wry humour and self-mockery delivering Bryson’s “origin story” at face value and ignoring what’s concealed beneath the bravado we so often adopt when asked for our story. (To be fair, we also often laugh at ourselves sincerely, and healthily, since this whole Transition Thing is pretty darn weird, however you cut it).

Was Bryson mildly problematic, being sexualised in the scene where she dresses as a delivery girl? Maybe, but her deception (that loaded term in anti-trans discourse) is in service of justice, not pleasure, and any cis female agent attempting a similar deception in a thriller would effectively have been exploiting the villains’ tendency to underestimate a woman, for which they’d be punished, accordingly, when she pulls a gun from under her skirt. A quarter century later, Lynch appears to be addressing and tacitly apologizing for any offence when he includes a memorable scene in the third season, AKA Twin Peaks: the Return, in which Agent Bryson asks Gordon Cole (played by Lynch), now at the very top of the FBI, how come she had a comparatively easy time when she transitioned, after some initial difficulty. His response “I told those clowns to Fix Your Hearts or Die” has become a powerful slogan of trans allyship deliberately delivered by the man himself. I don’t have space to rehearse the argument here but I’ve written elsewhere about how the many kinds of “freaks” found in his work who abound in European fairytales and Gothic fiction and America’s own Southern Gothic are generally reclaimed and come to seem more like rounded characters in his work after a few minutes screentime, mobilizing traditional symbolism for sure (the Dwarf and the Giant, most obviously) but also pushing against prejudices against the disabled or neurodivergent or gender nonconforming, whereas Lynch is more likely to take figures at the heart of the American psyche – bourgeois cis-het people – and render them absurd or grotesque, sometimes by using one of his signature shots: holding a peculiar expression a little too long and too close for comfort. Denise Bryson falls into the former category: a figure whose place in American culture would have been in a circus sideshow as late as the first half of the 20th century (as in the novels of Carson McCullers or Robertson Davies), but who can be optimistically but not implausibly imagined working for the DEA by the end.

In short, Twin Peaks is the place that seems initially weird because cis-het people behave (tacitly) like Trans People (…without anyone clocking the fact) but becomes a place we all love - where the Cis-Het Male embodiment of justice and order Agent Cooper actually considers moving “when all this is settled” - and where the one out Trans Woman can be a hero(ine) because, goshdarnit (as Lynch might say) being out as your true self, whoever s/he is, is a kind of heroism. And that’s not just a moral for (Gender-)Queer folk like Denise but for Cis-Het people like Coop: at a time when irony and apathy were on the rise, revealing your “true self” might mean being sentimental and loving and actually showing you care.

[1] Quite a lot more, in every case, even if you sift out those of us engaged in sex-work (i.e. Afro-Caribbean trans women are more likely to be murdered than any other category of person in the US and Europe, and bring up the “averages” for many crime statistics but white trans women are still more likely to be assaulted and murdered than white cis women).